Memories of Lake Balkhash 1

Aigerim Kapar,

Daughter of the Steppes, from the Argyn Tribe

2050, Kazakhstan, Almaty—the largest city in the Lake Balkhash basin.

A storm again—a dusty, prolonged, and toxic storm. Breathing in Almaty without a protective mask is impossible. We've forgotten what open windows mean and replaced them long ago with metal shutters. The last storm lasted about a week; in its suffocating haze, it's easy to lose your bearings in both time and space. Permanent darkness engulfs the city, and dunes can block roads within hours, making venturing outside perilous. Electricity is sporadic, and I rarely manage to charge my devices. Perhaps it's time to order an hourglass—people say it helps to feel and measure time. If, of course, there's money left after paying for water. Technical water circulating in the apartment is cheap, but drinking water is more expensive than oil.

It's hard to imagine, but just ten years ago, Almaty was a thriving, green city in the Zhetysu Valley at the foot of the Alatau mountains. The main environmental concerns had been smog and air quality. Mountain rivers flowed through the city, merging into the transboundary Ili River, which carried its waters to Lake Balkhash—a pearl of the Kazakh steppes.

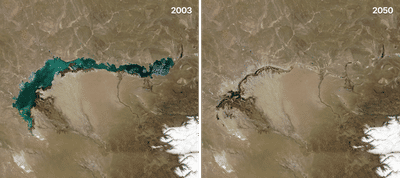

Lake Balkhash was located in central Kazakhstan, 300 km from Almaty, an unseen climate regulator for the city and the backbone of its ecosystem. Shaped like a human liver, it metaphorically hinted at its life-sustaining role in the arid region. One half of the lake was fresh, the other saline. Its waters were piercingly turquoise—a mirage of color and taste in my memory. Sadly, 2040 marked the irreversible death of Lake Balkhash, formerly the 14th largest lake in the world. Within five years, it vanished—a fate sealed by its average depth of only six meters and a vast surface area exceeding 16,000 km². Rising temperatures made it evaporate as if it were boiling. The Ili River, supplying over 70% of the lake's inflow, dried up as the glaciers feeding it disappeared. The Lepsy and Karatal rivers were lost to the sands a decade earlier. Disrupting the delta's connection to Lake Balkhash triggered the collapse of its entire ecosystem.

The disappearance of Lake Balkhash (2003, 2050), based on NASA Earth Observatory

The lake's demise was primarily caused by human interference, exacerbating the climate crisis. Irresponsible use of Ili River waters by Kazakhstan and China, geopolitical tensions, Russia's neo-colonial policies in favor of building a nuclear power plant near Balkhash, and systemic corruption in Kazakhstan all played a role. Despite efforts by artists, scientists, local communities, and activists to prevent catastrophe, Lake Balkhash followed the fate of the Aral Sea, another victim of 20th-century colonial crimes.

Initially, the water deficit wasn't immediately felt. The Ministry of Water and Irrigation of Kazakhstan annually reported that the Ili River, flowing from East Turkestan (Xinjiang, China), provided enough water to maintain the lake's level at 341 meters above sea level. The optimistic news in autumn 2024 about the Kapshagay Reservoir on the Ili River being full for the first time in years was misleading. The increased water levels were due to rapidly melting glaciers. The Ministry of Ecology saw no significant problem in constructing a nuclear power plant by the lake. At the time of the 2024 referendum approving the plant in the village of Ulken, no studies were conducted on the lake's ecosystem or the plant's potential long-term impact. A 2012 McKinsey study, commissioned by the Kazakh government had already warned that Balkhash would lose up to 86% of its water by 2030. The projections understated the impact of the climate crisis; in practice, the fragile system of Lake Balkhash collapsed even sooner.

The Ili delta was the first to degrade. Even the ancient tugai trees couldn't withstand the changes. Species of animals and birds dwindled, with boars, Bukhara deer, and tigers reintroduced in the Ile-Balkhash Reserve disappearing again. The lake split into two parts—Eastern and Western Balkhash—separated by the Uzyn-Aral Strait, initially only two meters deep. Without a surface connection to each other or the rivers that once fed them, Balkhash dried up. The new Balkhashkum desert merged with the Moinkum, Betpak-Dala, Kyzylkum and Aralkum deserts—the latter formed from the dried Aral Sea. This created a vast toxic sand ocean stretching thousands of kilometers.

From Schulz, C., & Kleinschmit, B. (2023). Monitoring the condition of wetlands in the Syr Darya floodplain— How healthy are the Tugai forests in Kazakhstan? Forests, 14(12), 2305. – https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/14/12/2305

For years, I imagined a sustainable future for the Lake Balkhash basin, hoping its turquoise waters would continue to ripple, preserving ecosystems and local communities' collective memory. But as the climate crisis intensified, hope melted away proportionally, albeit with small fluctuations and surges. Now, winds carry grains of the lake's sands across the world—from Europe to Antarctica and Australia—reminding us of our shared, interconnected climate.

My care for Lake Balkhash began in 2020, alongside artists and researchers from the Artcom Platform. Together with local communities and experts from the northern shores, we launched the public initiative "Care for Balkhash." Despite dire predictions of the lake's disappearance by 2030, it was crucial for us to envision the future we desired. In 2023, I moved to Balkhash with artist and researcher Aigerim Tleubay to conduct the Art Collider x Balkhash Youth School, helping local youth create socio-ecological projects. We also began organizing the International Water-Climate Forum Balkhash-2024. Throughout the year, Aigerim and I, with the support of our team—Antonina van Lier, Karlygash Akhmetbek, Aigerim Ospan—and the local community, lobbied for the lake's interests with government officials, businesses, international organizations, and diplomatic missions. Our goal was to engage key stakeholders in preserving Balkhash's ecosystems. Tears and frustration marked those years—we constantly explained the lake's plight and the urgency of action.

Despite everything, the forum was held and supported by the Ministry of Water and the Ministry of Ecology. The region's largest business stakeholder and, at the same time, polluter becames its main sponsor. The corporation became deeply involved in preserving sustainable ecosystems and caring for the lake because their well-being depended directly on it.

The Ministry of Water announced before the referendum on the Balkhash nuclear power plant that a transboundary water agreement with China was forthcoming. However, after the positive referendum decision, the agreement never materialized. Negotiations had been ongoing for more than 20 years, during which Kazakhstan's representatives nearly succeeded in convincing China that Lake Balkhash was a natural object requiring a vital volume of water. The water allocation from the Ili River should consider the lake's needs rather than just per capita distribution. However, China refused to increase water volumes, arguing that the water was needed to cool nuclear reactors.

Drought came first. Agriculture became impossible, and the food crisis worsened as livestock perished. This was followed by poverty, hunger, and migration—people tried to leave wherever they could. However, not everyone was able to abandon their homes and the graves of their ancestors. With the "departure" of the lake, the copper smelter, mining operations, and nuclear power plant construction collapsed due to the lack of water and people. The gas from the factory chimneys no longer poisons the air, but everything that had settled to the bottom of the lake since the plant began operating in 1938 is now swirling in the air. Locals used to call it "Balkhash rain" when, on windy days, the city was blanketed with toxic dust from the tailings storage. Now, Balkhash rain covers the entire region.

The lake's "slow violence" began in the colonial period of the early 20th century with settler colonialism and the disruption of traditional ways of life. For millennia, nomadic tribes formed sustainable socio-economic systems and adapted to the arid climate. They considered themselves part of the ecosystem on which they depended, living in harmony without any desire to "conquer nature." In the 1920s, industrialization began here, including the exploration and extraction of metals. Against the local Kazakh nomadic tribes, the imperial tools of forced collectivization, artificial famine, and forced sedentarization were employed—a genocide that led to the disappearance of more than half the nomadic population of Kazakhstan by 1933. Lake Balkhash became a hope for salvation; nomads from the steppe flocked here, trying to survive. Yet, the builders of socialism, who arrived from various Soviet republics, had no concern for them. A monument to the famine victims near the lake's shores reads that over 55,000 people died in the Bertys Bay area close to the smelter. Those who survived were forced to settle and work in mines and quarries. The livestock population decreased by 90% due to collectivization, vegetation cover and soil degradation. Biodiversity also suffered from excessive hunting and was displaced from its habitats by extensive farming. On top of this, Soviet authorities decided to establish several GULAG labor camps near Balkhash and further militarize the northern lakeshore. Closed military towns and a missile test range were built, which served as Russia's radar shield against China until recently. The military eventually abandoned the area, as the lake's surface, critical for navigation systems, had disappeared. No one ever counted how many hazardous and toxic substances were dispersed over the steppe and lake or how much seeped into the groundwater. Now, it probably doesn't matter.

The latest significant drop in the lake's water level occurred in the 1980s with the construction of the Kapshagay Hydroelectric Station on the Ili River and the reservoir filling. Soviet propaganda always amazed me with its claims of innocence: "We didn't know; we didn't expect it; it just happened accidentally." Just as with the Aral Sea, when they introduced cotton production in Central Asia, they knew in advance that the "white gold" would cost the sea and the local people their health and future. The price of the industrial project on the Ili was the degradation of the Ili delta. Tugai forests withered, turanga groves sharply diminished, satellite lakes of Balkhash dried up, muskrats went extinct, and fish from the lake could no longer migrate upstream to spawn, among other consequences. The hydrological balance was broken. Civil society, politicians, members of the government, experts, and environmentalists did tremendous work in the 1990s and early 2000s advocating and developing a plan to preserve the lake. A state program for Lake Balkhash was even adopted, but it conflicted with the interests of businesses and officials.

The disappearance the Aral Sea. NASA Earth Observatory https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/AralSea

Unfortunately, it is not surprising that the colonial power of Kazakhstan did not learn anything from this situation. Capitalist interests were again prioritized, and we successfully "archived" the lake. Now, scientists are trying to restore the nomadic culture and economy, recalling nomadic routes, wells, and underground water sources. A Ministry of Adaptation has been established. We have a whole ministry where scholars learn from our ancestors how to adapt to climatic realities and revive the knowledge that was lost in the colonial storm.

Footnotes

- 1Memories are based on the collective work of the Artcom Platform on the initiative Care for Lake Balkhash.