The Temporal Occupation of Ukrainian Housing by russia

The last time I left Berdyansk was in the fall of 2021, just a few months before the full-scale invasion. I was walking to the train station under an unpleasant autumn drizzle, glancing around indifferently. Before leaving, I visited my grandmother. Soon, I would propose to my future wife, and we would start living together at her place in Kharkiv. There was no reason for me to return to Berdyansk in the foreseeable future, and it felt as though I was saying goodbye to my hometown, brushing the fur of my old dog Jessica, who still couldn't get used to life in my grandmother's kitchen. I would never see the dog I'd spent most of my life with again. Some time after the occupation, nearly deaf and blind, she wandered out ofmy grandmother's house and never come back.

In these years of full-scale war, I often have dreams of returning home. These dreams hold no memories of everyday moments—no visits with relatives or Jessica, no walks through my neighborhood with my best friend. Instead, moving through Berdyansk in my dreams is filled with anxiety that the Russians might discover me if I accidentally say "дякую" (thank you' in Ukrainian) instead of "спасибо" ("thank you" in russian) to a cashier at the pharmacy or reveal myself in some other way. At the same time, the dream is weighed down by guilt for deciding to return. It creeps in right after the delayed realization of where I am and how I got there.

By occupying my city, the russians also lay claim to my cognitive space, my imagination, and my dreams. The vast distance between Berdyansk and Kyiv, divided into rear, front, and occupation zones, makes no difference here. On any given night, regardless of my will, I might find myself there, panicking as I think about escape routes, running through familiar yet strangely altered streets. And upon waking, I finally remind myself not to forget to call my grandmother and ask how things are in her garden.

Colonial regimes behind contemporary invasions operate on multiple scales simultaneously, creating a dynamic suppression that stifles resistance across various spheres of life, thereby fostering a perception of the regime's totality. Imperial actions are inherently contradictory—destructive and constructive at once—but share a common objective: the seizure and exploitation of territories. As researcher Vlada Vazheyevskyy illustrates, the multi-layered practices of settler colonialism, honed over decades, are now actively employed in temporarily occupied Ukrainian territories (TOT). 1 In these regions, the industrial-scale destruction of populations intertwines with construction efforts; propaganda merges with logistics; and psychological operations are coupled with biometric technologies.

The interplay between the destruction of war and the construction of occupation reveals the home as a key site of overlapping occupation practices. The home functions as a site of memory, a space for connection, a sense of belonging, and source of safety—but also as infrastructure, a resource, a business, and a mere property. For the empire, the home is a resourceful site at every level. In her book on the foundations of Israel's occupation of Palestine, Hagar Kotef writes that the home, "…its structure, its ideology, the sentiments invested in it, the social textures within it and those of which it forms a part, are inseparable from the financial systems, policies, and moral economies of empire." 2 Indeed, the home becomes a central axis around which the empire's focus revolves— on emotional, military-political, economic, and bureaucratic levels. The occupiers' declarative manipulations of housing—a matter that might initially seem secondary amidst active hostilities—combined with russian legislative decisions and executive practices, are closely tied to deportation and settler colonialist methods. Organized to align with imperial objectives, the occupation's operations with the homes of the local Ukrainian populations impact economic, social, and political strategies and decisions on both the Ukrainian and russian sides.

For the local Ukrainian population under occupation, the home holds deep symbolic and psychological significance as a place of memory and continuity. Meanwhile, the occupiers have their own plans for the housing infrastructure of Ukrainian cities, leveraging it to shape perceptions, manage emotions, and influence imagination. Kotef references the mobilizing affect derived from the metaphor of home, which enables the systemic practice of "returning" homes at the expense of destroying others. 3 The metaphor of home is employed simultaneously in the discourses of both the oppressed and the oppressors. While Ukrainians frame their accounts of forced migration or deportation as stories of losing their homes due to occupation, russian propaganda billboards in the temporarily occupied territories celebrate the "return" of these lands "home." The forces accumulated in the mental, emotional, and physical spaces of home resist the expansion and entrenchment of the occupying regime, reconnecting with local histories predating the empire's arrival. The regimes, in turn, strive to break this reconnection, filling the occupied territories with their own narratives, told "from scratch," as if nothing existed before them. 4 Occupation rhetoric surrounding the metaphor of home is primarily aimed at reshaping the future by erasing the diversity of local pasts, which threatens the legitimacy of the occupiers' singular narrative.

This effort is exemplified by russia declaring September 30 a public holiday, celebrating the "reunification" of the so-called DPR, LPR, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia regions with russia. The All-russian Society for the Protection of Monuments produced a "documentary series" titled russian Heritage: Coming Home, which erases plural historical perspectives in favor of gratitude to the russian Empire and the USSR for founding and developing cities in southeastern Ukraine. In describing the purpose of the series, its creators appropriate the rhetoric of resistance, portraying themselves as victims of stolen history and territory: "Despite attempts to rewrite history, they [the so-called new regions] are an integral part of russian culture." 5 By propagating such narratives, the occupiers aim to install a technology of "self-erasure" of memory within the imagination of Ukrainians who live and act in hope of their cities' de-occupation. This approach is rooted in russia's long-standing practice of erasing local histories and constructing myths of russia's eternal claim to the newly occupied territories.

Imposing the idea of the infinity and inevitability of colonization on the temporarily occupied territories (TOT) is made easier by the fact that such colonization occurred in these regions centuries ago. The so-called "Novorossiya" project, initiated by 19th century russian empress Catherine the Great, was tied to the empire's expansion into the steppes of southeastern Ukraine, displacing Crimean Tatars and Nogais, assimilating Zaporizhian Cossacks, and subsequently settling the lands with colonizers. This concept was aggressively promoted as a political model to Ukrainians during the information war between russia and Ukraine, which intensified with russia's hybrid invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014. Russia's ideological framework of "return" or "reunification" extends beyond Ukraine. In the 18th century, Russians often referred to themselves as the "Great russians" and convinced themselves that not only Ukraine but also Lithuania and Poland would inevitably become part of the russian Empire. The will of the peoples and elites of these lands was never a consideration. 6 For example, the eastern territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, seized during Catherine the Great's partitions, were already referred to as newly "reunited" lands. Catherine herself ordered coins to be minted bearing her image, the two-headed eagle, and the motto Ottorzhennaya vozvratikh ("I have returned what was torn away"), under which the imperialist program of "gathering russian lands" was carried out. 7 According to the inscription on the coin, russia's imperialism is framed not as imperialism at all: nothing was taken away—something was merely "returned," as if it had always rightfully belonged.

Centuries ago, while displacing nomadic peoples and local ethnic populations, russia "brought the light" of European imperialism to southern Ukraine. Now, without any progressive facade, Putin and the Armed Forces of the russian Federation are bringing the darkness of oblivion to Ukrainian territories. This darkness includes the literal incineration of Ukrainian cities like Bakhmut, Vuhledar, Popasna, Avdiivka, and Maryinka, as well as the erasure of pre-russian local histories. Amid the need to build fortifications in response to Ukraine's 2023 counteroffensive, russian builders simultaneously found time to construct a multimedia "Historical Park 'russia—My History.'" In the series of complexes initiated by Putin, imperial dynasties are glorified, linking the imperial past with the contemporary war of aggression. 8 Browsing the project's website, it is hard to imagine Ukrainians or other local peoples being represented as equal and autonomous political subjects.

Instead, they are probably depicted as enemies, traitors, or, at best, laughable villagers. The destruction and simultaneous construction of museums, theaters, and homes by russians serve a single purpose: to force amnesia about what has been taken, and through this forced forgetting, to create a sense of reunification with the empire.

russians appropriate the home and its affective dimensions in parallel with their direct occupation efforts, not waiting for the end of active hostilities. Following settler colonial models like Israel, russia's destruction deliberately targets various infrastructures, one of which is the infrastructure of intimacy. This term, introduced by researcher Ara Wilson to bring a feminist perspective to the infrastructural turn, adds a new layer to the empirical analysis of infrastructure. It highlights the "networked quality" of infrastructures and provides insight into the affective interplay between power, social arrangements, materials, and technologies. 9 Palestinian geographer Sabrien Amrov, who uses the term infrastructures of intimacy in her context, demonstrates that the relational dynamics between multiple levels and entities within home-making activities are as intense as those found in telecommunications or utilities. A home encompasses not just "the actual physical building of the infrastructure that is the house," but also "the decorating, the social relations that take place in and around it," and the ways it is represented. 10 Amrov writes about "the spatial production of intimacy"—a set of affective attachments to places and people, shared awareness and communication, and configurations of tempo and sensation through relationality. This relational intimacy resonates deeply with the experiences of Palestinians and Ukrainians, whose connections to their homes embody these dynamics. 11 At this level, it becomes evident that what russia and Israel are engaging in is not merely military operations aimed at neutralizing military targets with collateral civilian losses. Instead, they are enacting what Olexii Kuchanskyi calls ontowar—"the destruction of what is alive in order to prevent what is possible." 12 By destroying and appropriating homes, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the russian armed forces seek to control the diversity of life that fills infrastructures of intimacy.

"In the interplay between the real and the probable," the territory of the home and its affective dimensions come under the control of numerous invisible bureaucratic-military logistical processes, such as passportization, filtration, deportation, and resettlement. 13 These practices draw from the legacy of Romanov imperialism, which researcher Willard Sunderland categorizes as Bureaucratic Colonization. When the russian Empire seized the southern steppes of Ukraine, it learned to manage the region's defiant nomads through colonial tutelage. Sunderland writes, "Required almost everywhere and seemingly capable of ameliorating the most incorrigible backwardness, bureaucratic paternalism usually involved providing material incentives for improvement, arranging for instruction by good example, and, last but certainly not least, defending against lapses or deviations through intense administrative vigilance and discipline." Today, russia is building a similar system of incentives and restrictions, organizing the movement of Ukrainians through territories under its control. 14

To access basic rights and services, Ukrainians in the TOT are forced to obtain russian passports. One of the key rights retained upon obtaining a russian passport is the right to property, including housing. Under imperial bureaucratic logic, when residents of the TOT change their identity documents, they are also required to update the ownership documents for their homes to reflect the new information. 15 Beneath this seemingly mundane bureaucratic procedure lies the machinery of settler colonialism. If a resident refuses to accept a russian passport and chooses to retain Ukrainian documents, or if they are absent from the TOT and unable to obtain a passport, re-registration of housing becomes impossible. In such cases, the occupiers declare the property "ownerless" (a term that clearly reflects imperial imagination: these places have no owner and never did). The homes are then sealed and "nationalized," meaning they are transferred to russian control. 16 The websites of puppet regional and city administrations frequently publish long lists of "ownerless" apartments in cities like Melitopol, Berdyansk, Prymorsk, and Mariupol, among others.

The list of 'ownerless property' on the street re-named after Daria Dugina in Melitopol. Screenshot from the website of marionette regional administration. URL: https://zo.gov.ru/news/show/vyyavlennoe_besxozyajnoe_imushhestvo78

Thus, a registry of apartments is created, which are temporarily or permanently allocated to russian military personnel, builders, engineers, teachers, and others. Meanwhile, destroyed housing is demolished, and residential complexes are built on the ruins. These new complexes are offered to local residents under mortgage plans, effectively forcing them to pay russians for rebuilding their homes, ensuring maximum financial return for the occupying authorities. 17 Partially intact apartments are sold by real estate agents to russians from Moscow, St. Petersburg, Krasnodar, and Nizhny Novgorod, where demand for cheap seaside apartments "with good ecology" surged following the full-scale invasion. 18

Ukrainian residents in the TOT often obtain russian passports to save their homes. To facilitate passportization, the occupying authorities simplify conditions. Meanwhile, restrictions and threats push Ukrainians to accept new russian passports. Residents who left the TOT before gaining access to the occupiers' passport offices and the documents needed for free movement are subjected to filtration. Those willing to return to the TOT and obtain russian documents to retain their property face lengthy inspections, lasting hours or even days. Their devices are scrutinized with forensic software capable of recovering deleted chats. 19 If entry is denied, Ukrainian citizens are subjected to biometric data collection (DNA) for precise tracking during future entry attempts. During the filtration process, FSB officers question Ukrainians about their views on the invasion, relatives serving in the Ukrainian military or special services, attitudes toward nationalist movements, and more. It is impossible to predict what might displease the FSB officers. Oftentimes, reasons for denial are not explained, and the accusations presented may be fabricated by blending real and falsified information. As of January 2024, it was reported that 3,800 people had been deported following unsuccessful filtration attempts. 20

More recently, Ukrainians can undergo FSB filtration upon entry into russia only at Sheremetyevo Airport, prolonging an already lengthy process. Each year, Ukrainians die while awaiting clearance at Sheremetyevo. In 2024, there have been reports of four such cases, with the total number of deaths in waiting estimated at 13–14 individuals. Relatives are informed of the deceased, and if they do not arrive promptly, the body may be simply "utilized," meaning cremated without further ceremony. 21 russian propagandists justify the harshness of these measures by citing the murder of propagandist Darya Dugina, for which they blame a certain Natalia Vovk, allegedly a Ukrainian from "Azov." However, the existence of this individual has not been confirmed by anyone other than russian propagandist media. 22 Although filtration measures were implemented in the first weeks of the full-scale invasion, they gained symbolic legitimacy only after Dugina's death.

The intensification of the filtration procedure reflects the evolution of the Soviet tradition of disorganized control over territories seized by russia. Researchers Svitlana Matviyenko and Daria Hetmanova explore this in their analysis of filtration camps in the occupied Donetsk region during the first year of russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Examining the spontaneity, randomness, and inexplicability of filtration processes, Matviyenko and Hetmanova posed the question: "What if, indeed, the purpose of the massive filtration machine is merely to produce two inexistent groups of people, just like the Soviet state used to produce its inexistent internal enemies in the 1930s, by falsifying linkages between the labels propagated by Russian state media or governmental officials and people's physical bodies?" 23 By forcing Ukrainian bodies to fit propagandist clichés, russia lays the groundwork for a paranoid bureaucratic erasure of Ukrainian presence in the so-called "new territories." Filtration categorizes the Ukrainian population into "enemies" and "spies," who are deported, and "russians by documents"—Ukrainians who, either out of loyalty or necessity, acquire russian passports. Meanwhile, as noted earlier, those who leave, fail to update their documents, or are deported are replaced by waves of military personnel, engineers, and wealthy russians. These newcomers share a financial dependency on the regime and a prolonged exposure to its propaganda. All of these deportation and settler technologies are employed by russia with one singular goal: to fabricate, at least on paper, a situation in which the local population appears homogenous—entirely russian.

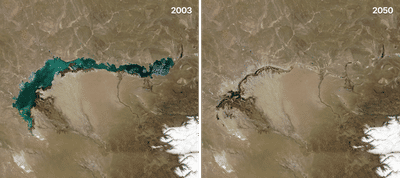

The destruction, confiscation, and construction of housing in the occupied territories are carried out at an accelerated pace for the same reason as colonial building "for the future," a pattern that can be retrospectively traced to the expansion of infrastructures in the Soviet republics. The histories of atomic, hydroelectric, thermal, and power stations built for the "welfare" of Soviet society—particularly the stories of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station—are marked by episodes of environmental destruction and the displacement of human settlements during their construction. During the full-scale war, the infrastructures inherited from the Soviet Union reveal their latent military potential, embedded in the destructive processes of their construction and exploitation. These infrastructures now represent one of russia's primary targets in its war against Ukraine.

Their disruption not only causes significant discomfort to the Ukrainian population, which russia seeks to demoralize through terror, but also inflicts physical damage comparable to the most devastating weapons. 24 25

Faithfully inheriting the practices of its former political body, russia rapidly builds over the ruins of the territories it occupies, intending to leave behind infrastructures that deplete and desolate Ukrainian land. Simultaneously, this sets the stage for future disputes among selters over the right to housing in the TOT after de-occupation, creating new pretexts for militarization and military actions. For russia, the home is a weapon—a Chekhovian gun hanging on the wall, destined to fire in the future.

Anna Engelhardt and Mark Cinkevich, in their video exploring infrastructural horror, evoke the russian occupation's infrastructures as imperceptible yet rapidly proliferating cable-tentacles of a synthetic uncanny parasite that, "while hoarding resources and siphoning energy away from the living, could not allow their host to die." 26 At one point in the video, the protagonist discovers one of these cables in their yard, snaking through a thicket toward a power station fueling russia's military machine, concentrated in an enormous airport. To this unsettling scene, I would add a jump-scare tied to infrastructures of intimacy and the home: after surviving torture in multiple filtration camps—where cables connect to gadgets and human bodies are classified as "ours" or "theirs"—a Ukrainian miraculously makes it back to their hometown. Upon reaching their home, they finds a russian standing behind the half-closed door, blocking entry, and shouting: "This is my home!"

A home under threat of seizure becomes part of an extractive infrastructure, exerting emotional control over displaced residents. The "domestication" of russians in the homes of neighbors who have fled or of Ukrainians who chose to remain in occupied territories functions as a form of slow violence, defined by Rob Nixon as violence that is "often not just attritional but also exponential, operating as a major threat multiplier; it can fuel long-term, proliferating conflicts in situations where the conditions for sustaining life become increasingly but gradually degraded." 27 By settling its citizens in Ukrainian homes, russia invests in a desired future where, even in the event of a Ukrainian victory, the occupied homes will serve as leverage for generating manipulative pretexts for renewed aggression.

In what appears to be a totally enclosed system, the Ukrainian Armed Forces' control over parts of the Kursk region has complicated russia's efforts to appropriate the affects of home and undermined the entire structure of its occupation imaginary. How can russia threaten entire populations with the occupation of their territories and the seizure of their homes when hundreds of russian settlements are already beyond its control? Explaining to its citizens the necessity of liberating their own territories becomes impossible without invoking concepts like independence, occupation, invasion, and evacuation—the very terms russian forces brought into Ukrainian homes, serving as constant reminders of the criminality of their invasion. russia has already provided a situational response by evacuating its citizens from the Kursk region to Ukrainian-occupied territories. 28 By combining evacuation with settler colonialism, russia seeks to convince both its own population and displaced Ukrainians that it will not relinquish its imperialist ambitions under any circumstance. This strategy reinforces the paradoxical narrative that even retreat or loss can serve the ultimate goal of consolidating control and sustaining the occupation dream.

Nevertheless, this decision will not reverse the situation created by Ukrainian forces, even if they are eventually compelled to retreat. Through their actions in the Kursk region, Ukrainians have once again challenged the imposed vision of their future as an occupied people, making it clear that russia's management of threats is fragile in the face of emerging subjectivity. The Ukrainian Armed Forces have torn an opening for this perspective, inviting co-operation. However, in the face of Western indifference, isolationism, and the foolishness masked by pacifism and a desire to avoid escalation, this act of holding ground becomes an act of excessive generosity. Any response from allies, even if it arrives today, will already be too late for the residents of Ukraine's temporarily occupied territories. And so, the cost of lost time rises ever higher. The suffocating tentacles of russian infrastructures grow heavier and longer, wrapping themselves tighter around possible futures.

Footnotes

- 1Vazheyevskyy, V. (2024, July 23). Russian military builders, an extension of and an efficient tool for the settler colonial state. UNITED24 Media. https://united24media.com/war-in-ukraine/russian-military-builders-an-extension-of-and-an-efficient-tool-for-the-settler-colonial-state-1352 . See also Runaition laboratory project and their video essay about the Russian colonial ruinization in the occupied Mariupol: https://www.instagram.com/p/C8hhtwctF2z/.

- 2Kotef, H. (2020). The colonizing self: Or, home and homelessness in Israel/Palestine. Durham and London: Duke University Press. P. 4

- 3Ibid. P. 4

- 4See more about Russian imperial erasure: Tsymbaliuk, D. (2022, June 15). Erasure: Russian imperialism, my research on Donbass, and I. KAJET DIGITAL. https://kajetjournal.com/2022/06/15/darya-tsymbalyuk-erasure-russian-imperialism-my-research-on-donbas/

- 5Всероссийское общество охраны памятников (2023, October 17).Русское наследие. Возвращение домой - Серия 1. Мелитополь. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xg8KleTf_Vk&list=PLFe0Zf20lOsiYkudnAXtZTXYeubkRcbIj&pp=iAQB

- 6Михаил, Де-Пуле. (1871). Станислав-Август Понятовский в Гродне и Литва в 1794–1797 годах (2-е изд.). СПб: Типография Майкова. С. 214

- 7Липранди, А. П. (1893). "Отторженная возвратих": Падение Польши и воссоединение Западно-Русского края. СПб: Калашниковская типография А. Л. Трунова

- 8Vazheyevskyy, V. (2024, July 23). Russian military builders, an extension of and an efficient tool for the settler colonial state. UNITED24 Media. https://united24media.com/war-in-ukraine/russian-military-builders-an-extension-of-and-an-efficient-tool-for-the-settler-colonial-state-1352

- 9Wilson, A. (2016). The infrastructure of intimacy. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 41(2), PP. 247–280.

- 10Amrov, S. (2018, May 3). Palestinian homes: Infrastructures of intimacy and the politics of representation. The Funambulist Magazine. https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/17-weaponized-infrastructure/37293-2

- 11Ibid.

- 12 Kuchanskyii, O. (2022, April 18). Digital Leviathan and his nuclear tail: Notes on body and the earth in the state of war. e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/463202/digital-leviathan-and-his-nuclear-tail-notes-on-body-and-the-earth-in-the-state-of-war

- 13Ibid.

- 14Sunderland, W. (2004). Taming the wild field: Colonization and empire on the Russian steppe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. P. 115

- 15Стасюк, І. (2024, September 10). Як українці втрачають житло в Маріуполі: їхні будинки зносять, новобудови купують росіяни. Хмарочос. https://hmarochos.kiev.ua/2024/09/10/yak-ukrayinczi-vtrachayut-zhytlo-v-mariupoli-yihni-budynky-znosyat-novobudovy-kupuyut-rosiyany/

- 16 Прокопчук, Е. (2023, November 22). Житло в окупації - як росіяни привласнюють майно українців. MRPL.CITY. https://mrpl.city/news/view/zrizayut-zamki-ta-ogoloshuyut-bezhazyajnim-yak-rosiyani-privlasnyuyut-zhitlo-v-okupovanih-mistah

- 17Янковський, О., & Бадюк, О. (2023, July 8). "Квартира за три мільйони в Маріуполі". Що цікавить жителів Росії на окупованих територіях? Радіо Свобода. https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/novyny-pryazovya-mariupol-rosiyany-kupuyut-zhytlo/32507088.html

- 18Стасюк, І. (2024, September 10). Як українці втрачають житло в Маріуполі: їхні будинки зносять, новобудови купують росіяни. Хмарочос. https://hmarochos.kiev.ua/2024/09/10/yak-ukrayinczi-vtrachayut-zhytlo-v-mariupoli-yihni-budynky-znosyat-novobudovy-kupuyut-rosiyany/

- 19Novosti.dn.ua. (2024, July 25). Можуть прочитати навіть видалені повідомлення: розвідка попередила українців про методи російських силовиків під час фільтрації. https://novosti.dn.ua/news/377875-mozhut-prochytaty-navit-vydaleni-povidomlennya-rozvidka-poperedyla-ukrayintsiv-pro-metody-rosijskyh

- 20Заборона. (2024, July 18). Аеропорт "Шереметьєво" став фільтраційним табором для українців. Їм просто не залишили іншого виходу. https://zaborona.com/aeroport-sheremetyevo-stav-filtraczijnym-taborom-dlya-ukrayincziv/

- 21Бадюк, О., & Щетина, Ю. (n.d.). Помирають під час фільтрації: через що проходять українці у "Шереметьєво" дорогою на окуповані території. Радіо Свобода. https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/novyny-pryazovya-filtratsiyi-sheremetyevo-povernennya-v-okupatsiyu/33117861.html

- 22Tsargrad.tv. (2024, May 9). Украинцы побежали из Европы в Россию: Фильтрация в Шереметьеве, как момент истины. https://tsargrad.tv/articles/ukraincy-pobezhali-iz-evropy-v-rossiju-filtracija-v-sheremeteve-kak-moment-istiny_997846

- 23Getmanova, D., & Matviyenko, S. (2022, October 17). Producing the subject of deportation: Filtration processes during the Russia-Ukraine war. Sociologica. https://doi.org/10.6092/ISSN.1971-8853/15387. P. 249

- 24Matvienko, S. (2022. April). Nuclear cyberwar: From energy colonialism to energy terrorism. e-flux Journal. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/126/460842/nuclear-cyberwar-from-energy-colonialism-to-energy-terrorism/

- 25Matvienko, S. (2023, June 8). Pollution as a weapon of war. L'Internationale. https://internationaleonline.org/opinions/1100_pollution_as_a_weapon_of_war

- 26 Engelhardt, A. (2023). Infrastructural horror. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZ6caZFF3fo

- 27Nixon, R. (2013). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge, MA, and London, England: Harvard University Press. P. 3

- 28Бадюк, О. (2024, August 21). «Евакуація на окуповане Азовське узбережжя провалена»: куди їдуть біженці Курщини? Радіо Свобода. https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/novyny-pryazovya-provalena-evakuatsiya-z-kurshchyny-na-okupovane-azovske-uzberezhzhya/33086199.html