Revealing the Landscape:

Mapping Cyclical History of Colonial Infrastructure of the Kakhovka Dam

Construction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station (1950s). Source: Central State Audiovisual and Electronic Archive of Ukraine.

From the sea to the desert to the forest

My grandmother cuts me off, pulling me back to the reality of wartime exchanges. 1 I often reflect on these conversations, thinking about what remains unspoken, hidden, or forgotten. Infrastructure is often invisible until it fails. A particularly tragic example occurred on June 6, 2023, with the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam—a catastrophe that not only caused immense human suffering but also stands as a major environmental disaster with far-reaching consequences.

Poem about the Sea

Still from the film 'Poem about the Sea' (1958) by Yulia Solntseva.

Two pivotal events shape the tragic history of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station. The recent one occurred on June 6, 2023, marking a moment of catastrophic destruction. The second spans a longer timeline, encompassing the years 1950 to 1956, during which the dam was conceived and constructed.

The plans to harness the power of the Dnipro River, one of the largest in the Soviet Union, and transform it into a navigable and energy-producing system began as early as the 19th century. During the Soviet era, the issue of irrigating the arid regions of southern Ukraine was a significant concern. This challenge was addressed in the 1930s through the "Big Dnipro" 2 plan, which called for the construction of several hydroelectric power stations and the creation of a cascade of reservoirs. The plan aimed to solve not only energy and irrigation problems but also improve transportation and other infrastructure needs.

During the five years of construction, over 250,000 hectares of land were submerged by the reservoir and 30 villages. Fertile arable land and vital floodplains between Zaporizhzhia and Kakhovka that supported the local economy were lost. The dam fundamentally altered the region's hydrology, slowing the river's flow with devastating consequences for the soil, flora, and fauna, resulting in a significant loss of biodiversity.

Through films and propaganda campaigns, a system of representation was emerging, crafting a unified image of nature reshaped by politics. Anna Neimark writes that in the Soviet era, the task of representing memory was often given to water works like canals, dams, and reservoirs. 6 The sheer scale and grandeur of these infrastructures elevated their symbolic role. They stood as monumental symbols, embodying a range of narratives: the assertion of human power over nature, the state's dominance over its peripheries, and, paradoxically, a memorial to what was lost.

Nevertheless, the landscape was transformed forever.

While histories often celebrate the technological triumphs of industrialization, they frequently overlook the exploitation of enslaved and colonized labor that made these revolutions possible. The story of the Kakhovka Dam—or any dam on the Dnipro River—is no exception.

Revealing the Landscape

Photography: Sonya Isupova, 2024.

In the early hours of June 6, an explosion destroyed critical infrastructure in southern Ukraine—the Nova Kakhovka dam.

Vast amount of water was unleashed downstream along the Dnipro river, flooding dozens of settlements.

Over the past year, I've been investigating the ecological impacts of this event, joining numerous amateur cartographers in documenting the war in my country. With my passion for robotics, I've created a map-drawing machine to explore innovative methods of mapping the uncertainties of Southern Ukraine's landscape. My practice engages with spatial representation, technology, and the role of local, embodied knowledge in counter-cartography.

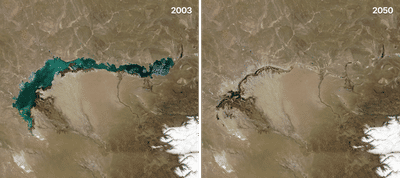

Together with Earth Scientist Anatolii Chernov, 7 we have analyzed satellite vegetation data following the Kakhovka Dam's destruction, tracking changes in the landscape on various dates like June 25, 1987 (37 years before the destruction), May 6, 2022 (one year and a month before the destruction), June 5, 2023 (the day before the destruction), June 18, 2023 (12 days after the destruction), and April 4, 2024 (11 months after the destruction).

Vegetation Data, Kakhovka Reservoir (1987–2024). Source: Sentinel Hub.

The machine continuously draws maps of the Ukrainian terrain on a large roll of paper, operating similarly to a pen plotter. Constructed with a mix of 3D-printed components, wood, and metal, it incorporates a CNC 8 circuit in its heart, allowing it to function like a CNC machine.

Photography: Stefanie Walk, 2024.

Interestingly, CNC machines are typically used in manufacturing to create metal and plastic components that consequently become parts of other machines. I decided to repurpose this tool to create cartographies instead, turning a device of production into a medium for exploration and storytelling.

After the gathering of this data the process of translation takes place. Pixels of the satellite image are translated into the geographical coordinate system, called g-code.

Sketches of the machine mechanism, 2024.

Photography: Sebastian Reinicke, 2024.

For decades, design theory and computation have been deeply intertwined, probing fundamental questions about how things function. Software is no longer just a tool for description and creation—it's a medium for understanding and conceptualizing.

Through the creation of custom-made software in collaboration with designer and software engineer David Héritier, we become mediators between the satellite platform and the map. We manage the signals that move through and between the two infrastructures: the satellite and the drawing machine. This process creates a vertical dimension 9—a straight line connecting the skies to the elongated maps produced as a result.

Landscape behind the map

Still from the film Revealing Landscape (2024) by Sonya Isupova.

As I work with the machine, I ask myself: What can I see through the printing process? Through building, constructing, soldering, 3D printing, spilling marker ink, tearing paper, and piecing maps together—can I see beyond the map to the landscape itself?

In this exploration, I attempt to rethink the map—not just as a critique of cartographic projections and their complicity in colonialism—but as a way to include what is often overlooked. Cartography has the power to erase certain realities, but it also has the capacity to reveal hidden truths. Through my process, I believe I am capturing something, thinking through something, and revealing something.

During the documentation stages of printing, something unique emerges: a special form of temporality. It takes approximately 10 hours to print a single map, a process requiring my constant supervision. I refill markers, change paper, and remain present, observing as the landscape gradually takes shape on the map. This meditative yet labor-intensive process forces me to slow down and pay attention. The machine compels me to witness. The maps demand to be seen.

In this back-and-forth of time, repetition, and ritual, the landscape appears. The results are long scrolls of paper and time-lapse videos—condensing 12 hours of printing into just four minutes. The videos erase the labor, amplifying the machine's movements. Yet I was there. I had to be there.

Technology, in this sense, becomes a means of revealing. My machine unveils the uncertainties of the landscape, just as the dam reveals the river as a technological system—a "standing reserve." This act of revealing is also a political act of witnessing and care.

With my deep preoccupation with the Kakhovka Dam—its history, the memories of my relatives, and the ecological crisis in southern Ukraine—I strive to uncover its many layers, its multitudes of cartographies, one by one. Much like the dam itself revealed the Dnipro River as both a resource for colonial power and, ultimately, a weapon, I seek to understand how its construction submerged historical landscapes, erasing and reshaping them. Its recent destruction has carved yet another wound into the already scarred region of southern Ukraine, amplifying the echoes of its troubled past.

Stills from the film Revealing Landscape (2024) by Sonya Isupova.

It serves as a stark reminder of the enduring impact of colonial infrastructures—not only on the landscape but also on its people and their memories. In this way, the dam embodies the cyclical nature of colonial power. From the colonial history of the land to the ecological impacts of the dam's construction and destruction, a complex, multi-dimensional map emerges. I am there to attempt to document it.

Presentation of the maps at La-Becque Open Studios. Photo by Aurélien Haslebacher, 2024.

Footnotes

- 1(2024, August). Excerpts from a private phone conversation with the author in Kyiv, regarding Nova Kakhovka.

- 2A plan to address the issues of irrigation and electrification in the arid regions of southern Ukraine proposed the construction of a cascade of hydroelectric power stations on the Dnipro River, starting with the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station (HES), as documented in the Central State Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of the USSR. Retrieved from: Central State Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of the USSR

- 3Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1894–1956) was a pioneering Ukrainian Soviet film director, screenwriter, and artist, recognized as one of the most influential filmmakers of the early Soviet era. Known for his silent trilogy Zvenyhora (1927), Arsenal (1929), and Earth (1930), Dovzhenko made key contributions to Soviet montage cinema. He also created wartime propaganda films, including Liberation (1940) and Battle for Our Soviet Ukraine (1943). Despite ideological pressures, his innovative work in the 1920s and 1930s established him as a cornerstone of Ukrainian and world cinema. Dovzhenko passed away in 1956, leaving a lasting cinematic legacy.

- 4Poem about the Sea (1958) tells the story of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station and the human dramas of those involved in its construction, both the participants and the victims. Oleksandr Dovzhenko wrote the script for Poem about the Sea while he was seriously ill. He completed the preparatory work and hoped to direct the film, but he passed away just before the first day of filming. His wife, Yulia Solntseva, completed the film after his death.

- 5Yulia Solntseva (1901–1989) was an actress and film director, best known for her work alongside her husband, Oleksandr Dovzhenko. As an actress, she debuted in cinema in 1924 and later worked at the Ukrainian Film Studio (VUKFU). She assisted Dovzhenko on several films, including Arsenal (1929) and Earth (1930), eventually stepping in as a director herself. After Dovzhenko's death in 1956, she completed his final film, Poem about the Sea (1958), marking her directorial debut. Solntseva went on to direct several films based on Dovzhenko's works, earning recognition for her contributions to Soviet cinema.

- 6Neimark, A. (2012). The infrastructural monument: Stalin's water works under construction and in representation. Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism, 9(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5749/futuante.9.2.0001

- 7Ph.D. in Earth Science from the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

- 8Computer numerical control

- 9Weizman, E. (2024, December 15). 1. Introduction to The Politics of Verticality. openDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/article_801jsp/