Saltivka Pine Forest: Landscape Mapping, 2024, digital collage by Liza Goncharenko ©

The Weaponization of Ecosystems: Historical and Contemporary Parallels

War is not fought solely on the ground of human lives or geopolitical ambitions; it is waged within the landscapes we inhabit, upon the flesh of the earth, and within the very systems that sustain life. Nature, so often conceived as a passive backdrop to human events, becomes, in times of conflict, both a tool and a target. This entanglement between warfare and ecosystems, where forests burn, rivers are poisoned, and soil is rendered barren, exposes a deep interdependence: the lives of nations and individuals are already intertwined with the life of the earth. 1

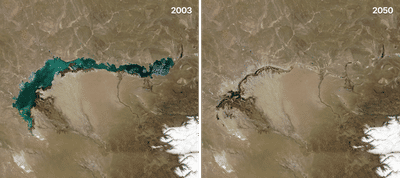

russia's invasion of Ukraine, with its deliberate devastation of forests, water supplies, and agricultural lands, compels us to reflect on this grim phenomenon. From the catastrophic destruction of the Kakhovka Dam to the targeted attacks on Ukraine's 'breadbasket,' 2 the current war reveals how ecosystems are weaponized not just for strategic advantage but as acts of domination over a people and their land. Such tactics are not new; they echo the scorched-earth policies of Nazi Germany, the chemical warfare of Vietnam, and countless other instances where land, water, and air became extensions of military ambition.

Illustration by Liza Goncharenko ©

To view these acts through the lens of history is to uncover a recurring truth: warfare is not only the domain of armies but also of the natural world itself, where landscapes and ecosystems are enlisted in the service of violence. Yet, nature is not a passive victim. It resists. It reclaims. As philosopher Anna Tsing reminds us in The Mushroom at the End of the World, the earth is alive, teeming with forces that exceed human control, sometimes even subverting our intentions. 3 This essay traces the weaponization of ecosystems across history, revealing both the deep scars left by militarized nature and the resilience of the more-than-human world.

Nature as a Weapon: From the Forest to the Field

The weaponization of nature is as old as war itself. Armies have long recognized that to destroy people, one must destroy the systems that sustain them. Water supplies are poisoned, crops are burned, and forests are felled to deny refuge or sustenance to an enemy. 4 These acts, horrifying as they are, are not merely tactical but symbolic: they seek to unmake the relationship between people and the land they call home.

During World War II, Nazi Germany's scorched-earth retreat across Eastern Europe epitomized this logic of destruction. As they abandoned occupied territories, the Nazis destroyed infrastructure, burned farmland, and devastated ecosystems to leave nothing usable for advancing Soviet forces. The aim was not only to slow the enemy but to erase the possibility of life in the wake of their withdrawal. What they left behind was a land stripped of its vitality, where soil turned to dust and forests smoldered.

Centuries earlier, the Dutch employed a similar but inverted strategy during their resistance against Nazi occupation in World War II. By flooding vast tracts of land, a tactic known as "inundation," they transformed their landscapes into an impenetrable barrier. Here, nature became an accomplice in survival, a shield against invasion. The Dutch tactic reminds us that ecosystems are not passive victims; they are active participants in the theater of war.

Illustration by Liza Goncharenko ©

Vietnam: When the Sky Rains Poison

The Vietnam War marked a new era in environmental warfare, one that brought the full weight of industrial science to bear on the natural world. The United States' use of chemical defoliants, particularly Agent Orange, sought to strip the Viet Cong of jungle cover while destroying their agricultural base. 5 This strategy turned forests into battlefields, converting lush ecosystems into desolate wastelands.

As Alfred W. Crosby discusses in Ecological Imperialism, the destruction wrought by Agent Orange was not only a tactic of war but an extension of colonial logic. Just as European colonizers transformed ecosystems to favor their settlement, the United States reshaped Vietnam's landscapes to suit their military objectives. 6 The result was a landscape unmade, where rivers were poisoned and the air carried invisible toxins that lingered long after the fighting ceased.

The consequences of Agent Orange endure. Decades later, Vietnamese communities continue to suffer from its chemical legacy: birth defects, cancer, and an environment struggling to heal. The war did not end with the withdrawal of troops; it lingered in the soil, in the water, in the bodies of the living. 7

Ukraine: The Ecological Battleground

The russian invasion of Ukraine has brought the weaponization of nature into stark relief once again. From the beginning of the war, deliberate environmental destruction has been a central strategy. The destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in 2023 was a defining moment, unleashing floods that submerged towns, devastated farmland, and polluted water supplies. This act, while catastrophic for civilians, was a calculated maneuver to destabilize Ukraine's infrastructure and deny its people the basic means of survival.

Beyond the dam, russia's military actions have targeted Ukraine's vast agricultural lands, often referred to as the "breadbasket of Europe." Fields have been mined, irrigation systems destroyed, and soil rendered unusable by contamination. The deliberate targeting of these resources is an attack not just on Ukraine's economy but on its identity: a symbolic assault on the nation's ability to sustain itself and its people.

These tactics bear a chilling resemblance to historical precedents. The scorched-earth strategies of World War II and the ecological manipulation of Vietnam reveal a continuity in the logic of environmental warfare: to control a people, one must first control, or destroy, their land.

Ecological Imperialism and the Domination of Nature

In Ecological Imperialism, Alfred W. Crosby offers a framework for understanding the deeper implications of these acts. Crosby argues that the history of conquest is inseparable from the history of ecological transformation. Invading powers have always sought to dominate not just people but the environments they inhabit, reshaping ecosystems to suit their needs and ambitions. 8

This logic persists in modern warfare. In Ukraine, the destruction of forests, water systems, and farmland reflects a strategy of ecological domination, where the land itself becomes a battleground. Yet, as Crosby's analysis reminds us, such domination is never absolute. Nature resists. It adapts. It continues to grow, often in ways that subvert human control. 9

The agency of nature becomes even more apparent when viewed through the lens of Anna Tsing's work. In The Mushroom at the End of the World, Tsing explores how life persists in the ruins of capitalist and imperial devastation. Her insights reveal a critical truth: ecosystems are not passive victims but active participants in the aftermath of destruction. Forests regrow. Rivers find new paths. Even in the most devastated landscapes, life continues to emerge.

Toward a Decolonial Framework of Environmental Care

If war devastates ecosystems, then peace must involve their restoration. Yet restoration cannot simply be about returning nature to its "original" state, a state often mythologized and misunderstood. Instead, it requires a decolonial framework of care that recognizes the agency of ecosystems and prioritizes their health alongside human recovery.

This approach urges a shift from ownership to stewardship, imagining landscapes not as commodities but as kin. The deliberate pollution of ecosystems weaponizes the most intimate relationships between life and land, transforming environments into sites of prolonged suffering where toxins linger in soil, water, and air, long after human cataclysms subside. 10 In Ukraine, where rivers are contaminated, forests burned, and soil saturated with remnants of war, recovery must transcend technical repair; it must involve an act of cultural and ecological reciprocity. The land, much like its people, carries scars that are both physical and symbolic, demanding rituals of care that honor its role in survival and renewal.

Artistic interventions can play a vital role in this process, transforming recovery into an act of remembrance and reimagination. Ceremonial gestures that cleanse polluted waters, tapestries woven with the charred remnants of forests, and collaborative efforts to replant native species not only restore ecosystems but reconnect communities to the land as a living, breathing entity. 11 Such practices embody a decolonial ethos, rejecting the logic of dominance and exploitation in favor of relationships grounded in mutual respect and care. This framework envisions a future where human and ecological recovery are inseparable, fostering a shared resilience that emerges not from erasing the scars of war but from embracing them as part of an intertwined journey toward healing.

In Ukraine, the work of restoration will be monumental. Forests must be replanted, rivers cleaned, and soil rejuvenated. But beyond the technical challenges lies an ethical imperative: to treat the land not as a resource to be exploited but as a partner in recovery. This perspective shifts the focus from domination to collaboration, from exploitation to care.

Such framework acknowledges the scars left by war not only on human communities but on the more-than-human world.

Illustration by Liza Goncharenko ©

It demands a reckoning with the past, a recognition of the ways in which ecosystems have been manipulated, weaponized, and sacrificed in the pursuit of human ambitions. Only by addressing this legacy can we hope to build a future where nature is respected as a partner in peace rather than a victim of war.

The weaponization of ecosystems is a haunting reminder of the entanglement between human war and the natural world. From the scorched-earth policies of Nazi Germany to the chemical warfare of Vietnam and the ecological destruction in Ukraine, history reveals a persistent pattern: to wage war is to wage it against the earth itself.

Yet nature is not a casualty of human violence. It resists. It reclaims. In the ruins of war, life persists, challenging the logic of destruction and offering a vision of renewal. To recognize this resilience is to see ecosystems not as passive backdrops to human events but as active participants in the unfolding drama of history.

In this recognition lies the hope for a new ethic of care—one that honors the agency of the more-than-human world and prioritizes its recovery as part of the broader work of peace. For in the end, the fate of nations and the fate of the earth are inseparably bound. To restore one, we must restore the other.

BIO:

Lelyzaveta (Liza) Goncharenko is a Ukrainian licensed architect, urban designer, and researcher based in Brussels. She holds an MSc in Architecture from KU Leuven (2019) and a BArch from KNUCEA (2015), with additional Urbanism and Landscape Architecture studies at Lisbon University. She has worked in architecture offices across Kharkiv, Stockholm, Antwerp, and Brussels. She was the National Contact for Ukraine at the European Architecture Students Assembly. She co-curated the Residency SESAM Poliklinika in Slavutych, Ukraine. She developed a graphic novel about green sustainable initiatives in New York City at the Institute for Public Architecture. Liza is actively involved in research on Ukraine's ongoing resistance and inter/post-war reconstruction efforts.

Footnotes

- 1 Brauer, J. (2009). War and nature: The environmental consequences of war in a globalized world. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- 2Bazdryieva, A. (2022). No milk, no love. e-flux Journal, (127). Retrieved from https://www.e-flux.com

- 3Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 4Brauer, J. (2009). War and nature: The environmental consequences of war in a globalized world. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- 5Martini, E. A. (2012). Agent Orange: History, science, and the politics of uncertainty. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- 6Crosby, A. W. (1986). Ecological imperialism: The biological expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 7Martini, E. A. (2012). Agent Orange: History, science, and the politics of uncertainty. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- 8Crosby, A. W. (1986). Ecological imperialism: The biological expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Matvienko, S. (2022). Pollution as a weapon. Critical Inquiry. Retrieved from https://criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu

- 11The Red Nation Podcast. (2020, December 29). Indigenous architecture: Building historical consciousness. The Red Nation Podcast. Retrieved from https://therednation.org