Adaptive Violence: How War Transformed Institutions and Art

"You need to ask to stop at Svitlyi Shliakh Street"—this was the answer I got from a minibus driver when I asked how to get to Izolyatsia in Donetsk in 2013. At that time, Izolyatsia was a cultural space located on the premises of a factory that produced insulation materials. The primary goal of this platform was to engage with the local context of the Donbas region through art and to involve both renowned international artists and the Ukrainian art scene in its projects.

In a short time, Izolyatsia became a meeting place — for artists from various regions of Ukraine, local cultural workers, and a wider circle of viewers. My own encounter with Izolyatsia happened during the project Pulse Room by Mexican-Canadian artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer — a participatory project where, using a special sensor, a viewer's heartbeat was captured, making a massive empty hangar flicker in sync with their pulse.

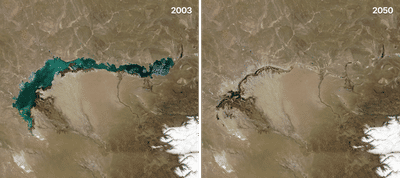

Pulse Room exhibition in Izolyatsia. Donetsk, 2013. Source: Izolyatsia website

I still remember the exhilarating feeling I had as my 17-year-old self — it seemed as though this vast, superhuman space was being reappropriated by me and, instead of feeling alienated, became warm and close. In 2021, I saw that hangar again, but this time only in photographs. The place that once pulsed with my heartbeat (was me) was now filled with russian military equipment.

Military equipment in a former territory of Izolyatsia in Donetsk. Source: Telegram-channel Donetskiy traktorist (A Donetsk tractor driver)

***

On June 9, 2014, armed militants, including russian military personnel, seized the premises of the cultural center Izolyatsia. This event occurred during the third month of the occupation of parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and the fifth month following the annexation of Crimea. At that time, russia was not interested in open armed conflict and was conducting a hybrid war. The events in the East were referred to as a "civil war in Donbas" or a "conflict" in which russia was "assisting" the formation of young "republics." According to the foundation's team, who found themselves in exile, the center's territory was to be used by military formations as a storage site for humanitarian aid arriving from russia, as well as a "base for training militants, a prison, an execution site, and a warehouse for stolen vehicles." 2

Representatives of the occupation administration claimed that they would use the Izolyatsia as a storage site for humanitarian aid arriving from russia. However, very quickly, Izolyatsia becomes a black hole in the city, to end up "at Izolyatsia" meant to be subjected to torture and, quite likely, never return. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), from 2014 to 2021, detainees at Izolyatsia were subjected to the following methods of torture 3:

- Beatings, punches, and kicks;

- Beatings with wooden or metal rods, weapon butts, or batons;

- Suffocation using plastic bags and waterboarding techniques;

- Electric shocks applied to limbs, fingers, toes, and genitals;

- Mock executions;

- Blindfolding and handcuffing for several days;

- Pouring cold water on detainees during interrogations;

- Forced nudity and other forms of sexual violence;

- Verbal insults and threats, including threats of sexual violence and violence against detainees' relatives.

As of the drafting of this report, hundreds of people passed through the Izolyatsia prison. Primarily, this included Ukrainian military personnel and local residents suspected of espionage or "crimes against national security." At the same time, the prison also held "members of armed groups and other actors of the so-called 'Donetsk People's Republic' accused of committing common or military crimes." 4 The reasons for ending up "in the basement" were highly varied: coercive attempts to force collaboration, having a Twitter account, using Ukrainian as the selected language on phone, or confiscating a business.

Journalist and writer Stanislav Aseyev, a former prisoner of "Izolyatsia," was detained for something as minor as quotation marks in his reports. These quotation marks were used in the phrase "Donetsk People's Republic," implying its lack of recognition by the international community and even by russia. Such quotation marks immediately resulted in a signature on a document proudly declaring the capture of a "criminal who denies the state sovereignty of the DPR." 5

In their terminology, pro-russian forces often resorted to words directly referencing the Soviet punitive structures of the NKVD 6 — spy, enemy of the people, fascist, etc. These terms remain part of russian propaganda today. The main goal of these actions was to instill paralyzing fear, making any acts of resistance impossible.

***

In Hito Steyerl's text A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War, 7 she refers to an episode where a World War II tank, previously a monument, was taken off its pedestal and used to attack a Ukrainian checkpoint in Ulyanovka, Krasnoarmiisk (now Pokrovsk) district. Steyerl describes the pedestal as a kind of repository that preserves the war potential of the object (I would add, both in a symbolic and literal sense).

This story, along with the rapid transformation of Izolyatsia's premises into a prison, suggests that despite being repurposed, military infrastructure retains its potential to quickly "revert" to a militarized object. Similarly, the complex of buildings that housed the insulation materials factory was initially designed as a strategic enterprise. The insulation materials factory itself, founded in 1955, was equipped with a built-in nuclear defense system — a sprawling network of underground rooms and passages stocked with supplies of food and water. Moreover, it "produced mineral wool for industrial thermal power stations in the USSR, as well as for the military, aviation, shipbuilding, and space industries." 8

It is essential that in the USSR, almost every factory was associated with the military complex in some way or another. And the Isolation Materials Factory in Donetsk was no exception. In this sense, the Izolyatsia space underwent a double tragic transformation – firstly, gentrification, i.e., the turning of a decayed and crisis-ridden industrial factory into a post-industrial centre of contemporary art. This transformation seems a general trend, as former militaristic infrastructures often become art centres. For example, ZKM | Center for Art and Media is located in a historical industrial building in Karlsruhe, Germany, that formerly housed a munitions factory. One of the largest exhibition spaces in Ukraine – Mystetskyi Arsenal, also has a history of transforming the space from a militaristic one into a contemporary art venue. Mystetskyi Arsenal is housed in a building originally intended as a workshop for manufacturing, repairing, and storing ammunition and cannons.

However, the reverse transformation – from the centre of contemporary art to the militaristic infrastructure of the prison – raises the question of how civil and militaristic infrastructures are fused in modernity and how, in the case of occupation, military takeover, they can once again be reclaimed and transformed into an infrastructure of violence.

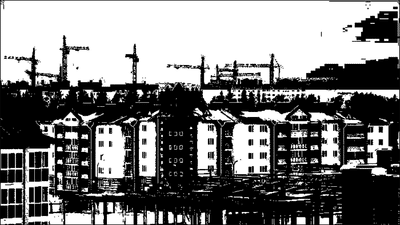

The architectural organisation of the factory as it was laid down in the USSR in the 1950s, including remoteness from the city centre, an enclosed area, and presence of cellars that could serve as bomb shelters for factory workers. From the memoirs of Stanislav Aseyev, who spent 2017-2019 in Izolyatsia prison, "At that point in time, there were eight ordinary multi-prisoner cells in the Izolyatsia, two disciplinary seclusion cells, one basement-bomb shelter for holding prisoners, and a single cell adjoining it, as well as several torture cellars. Three of the eight cells were women's cells. The maximum number of inmates held simultaneously in the Izolyatsia could reach approximately 80 people." 9

The fenced-off territory, controlled entrances and exits — all of this enabled the space to become autonomous and tightly controlled. The rapid transformations and "new purpose" of the infrastructure of the art center were described by one of Izolyatsia's former prisoners. The basements, once used for exhibitions, were transformed into cells with makeshift beds and surveillance cameras. Former office spaces were repurposed to house military leadership. The café area was turned into a dining hall for the military, while the space beneath it was used for interrogations. The hangars on the center's grounds, previously utilized for exhibition projects, were converted into weapon storage facilities and shooting ranges. 10

Plan of Izolyatsia prison. Source: Ukrainska Pravda, 2019

***

"They say this was almost a world-class museum that we took over. Considering what kind of art it was, it could not remain untaken, as the things that were being propagated here to corrupt the people of our republic are, to me, not art and cannot be considered art. [...] These are sick people creating and showing things to other sick people. [...] In the territory of the DPR, such art, as well as drug use will be punished. [...] These are people who hate everything Slavic. Everything Russian." 11

Still from Leonid Baranov at Izolyatsia. Source: Izolyatsia Must Speak

This is how Leonid Baranov, the acting head of the DPR's Ministry of State Security and the Special Committee in charge of contemporary art, commented on the seizure of Izolyatsia to russian journalists. Standing against the backdrop of a russian flag, he talks about the activities of Izolyatsia and its "harmful" influence. As an example of such "degenerate" art, he showcases a book by a well-known Ukrainian artist from Kharkiv, Boris Mikhailov, Look at Me I Look at Water.

In his "speech," he postulated authoritarian values, leaving no room for freedom or the multiplicity of perspectives — which, by its very nature, art embodies. He proclaimed a single correct direction of thought and existence, where all others are subject to eradication, with only the authorities being capable of determining their "rightness." Everything "undesirable" must be physically destroyed within this framework— the human body and the artwork.

Since many artists worked with the context of the former factory, the works they created were literally embedded into its structure. Consequently, all of these works were lost. The foundation provides the following list: works by Daniel Buren (France), Cai Guo-Qiang (China), Leandro Erlich (Argentina), Kader Attia (France), Pascal Marthine Tayou (Cameroon-France), Lubov Malikova, Zhanna Kadyrova, Hamlet Zinkivskyi (Ukraine), and others. 12

The fate of some art objects is known only through publications in pro-russian media or reports by russian news outlets. For instance, the works of Ukrainian artist from Crimea, Maria Kulikovska, Homo Bulla – Human as Soap Bubble 13—soap sculptures intended to gradually deteriorate under natural conditions, symbolizing the fragility of the human body—were moved to a hangar where they were turned into shooting targets. 14

Another prominently destroyed artwork was Pascale Marthine Tayou's Make up… Peace! 15 The installation, one of the most recognizable symbols of Izolyatsia, took the form of a lipstick placed atop a pipe from the factory's former boiler room. The lipstick served as a symbolic monument to the women who rebuilt Donbas after World War II. After the seizure of Izolyatsia, the fate of the artwork remained unknown for some time. In 2015, the lipstick disappeared from the factory grounds. Later, pro-russian social media groups on VKontakte published a video showing militants blowing up the installation. In her article From Postmodern Art to Stalinism: Donetsk's Culture Reimagined Kateryna Iakovlenko wrote, "Such an act of destruction constitutes not only violent work with memory and public space; it is a performative action, through which public demonstration and the strengthening of power proceed." 16

Acts of destruction grew even more brutal and pronounced in 2022 with the onset of russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2020, the Izolyatsia team decided to return to the East and resumed their activities in Soledar, a city in Donetsk Oblast. For a year, the foundation organized art residencies, actively engaged with the local community, and began planning the revitalization of the city's cultural center. With the start of the full-scale invasion, the foundation's office was repurposed by local volunteers as a coordination hub and a storage site for food, medicine, and hygiene supplies. In June, due to escalating security concerns, the office was closed, and the team evacuated. For a long time, the foundation did not know whether the building they had worked in had survived. Only later did local residents share photographs showing the destroyed structure. In an interview with Vilne Radio, Mykhailo Glubokyi, the development director of the foundation who had worked at Izolyatsia during its time in Donetsk, aptly summarized what I would like to leave as a conclusion:

"This is a deeply symbolic story for us, one that takes us back to the events in Donetsk. Of course, it's a symbol of what has happened to us for the second time. And it's a symbol of what happens with the arrival of the 'russian world.' The transformation of our cultural center in Donetsk into an illegal prison and the destruction of all cultural initiatives in Donbas since 2014 is emblematic of this reality." 17

Sculpture by Anton Logov 'Angel of Soledar' near the building with the office of the IZOLYATSIA Foundation, Soledar. Photo from occupation sources

***

With the onset of the full-scale invasion, it became clear that the actions committed with the support and participation of russian military forces at Izolyatsia were not isolated incidents. This is a systematic strategy in which culture is a significant target, and its destruction and theft are acts of subjugation. A few examples of the destruction and looting of cultural institutions during the full-scale invasion are worth recalling: the Historical and Local History Museum in the village of Ivankiv in Kyiv Oblast, which housed works by Maria Prymachenko; the Hryhorii Skovoroda Museum in Skovorodynivka, Kharkiv Oblast; the looting of the Kherson Art Museum and the Kuindzhi Art Museum in Mariupol. Beyond theft and destruction, in occupied cities, as in Donetsk in 2014, illegal detention facilities appeared, along with thousands of testimonies from people who were subjected to repeated torture, including electric shocks. This is russia's colonial ambition: to erase all traces of otherness and replace them with its own or to rename and appropriate them.

Anton Karyuk. 'My Anti-tank Hedgehog,' 2022. Photo by Oleksandr Popenko

Is war truly the end of art? In moments of such intense violence, it may seem so. Yet, despite its fragility, when reality appears to overwhelm any attempt to describe it, art undergoes a transgressive transformation—from self-denial to direct action. Not only do artists reshape themselves, but art institutions do as well. At the start of the invasion, galleries and art centers, such as the YermilovCentre in Kharkiv or the Lviv Municipal Art Center, became bomb shelters, refuges for internally displaced persons, or, like Izolyatsia in Soledar, humanitarian hubs. In terms of art itself, artists initially employed a strategy of art-as-testimony.

Over time, they transitioned to finding new mechanisms of resistance, where producing art often became a framework for raising funds or delivering necessary equipment for military needs. Examples of practices supporting the military include projects by artists Zhanna Kadyrova, Anton Karyuk, and charity auctions organized by the self-initiated group Silent for Deafness (a project by serviceman and artist Oleksandr Len and curator Anastasiia Kuzmenko). At the start of the full-scale invasion, artist Zhanna Kadyrova, who was forced to relocate from Kyiv to Zakarpattia, created a series of sculptures from river stones resembling traditional Ukrainian bread — palyanytsia. At the same time, the word became a linguistic marker for identifying "friend or foe," as russian soldiers were unable to pronounce it correctly, thereby exposing themselves. All proceeds from the sale of Palyanytsia (over seven million UAH) were donated by the artist to support the military.

In his work My Anti-Tank Hedgehog (2022), artist Anton Karyuk references the repurposing of anti-tank hedgehogs, originally museum exhibits from the World War II museum, which regained their function and were used to defend Kyiv at the start of the invasion. The artist produced 68 replicas of these hedgehogs in smoky quartz, donating all proceeds from their sale to military needs. In the case of Silent for Deafness, the self-organized initiative brought together a community of artists willing to contribute their works to charity auctions. This approach created, on the one hand, a narrative framework — a space for reflecting on pressing societal issues and giving young artists an opportunity to showcase their work — while, on the other hand, raising funds for the Rubizh battalion, where Oleksandr Len serves.

Beauty studio. 'Dreamcatcher,' 2023. Photo by Arsen Dzodzaev

Another strategy involves reconfiguring the very process of creating art. These practices can also be seen as a reassembly of institutions and grant systems, which are unable to allocate funds for military needs. For example, within the framework of the exhibition Even If (2023) at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture (DCCC), the group Beauty Studio presented the project Dreamcatcher, which addressed the challenges faced by volunteers in their work. The group itself was formed in Mykolaiv in 2022 to support volunteer efforts in the Mykolaiv and Kherson regions. The artwork took the form of a closed labyrinth constructed from found materials. Viewers could explore its interior via a camera mounted on a remote-controlled toy car, with its movements visible through FPV drone goggles. After the exhibition concluded, the goggles and the artists' fees were donated to support military needs.

Artist Maksym Khodak, in his work Dove of Peace Emoji (2024) for the Ukrainian Paradise exhibition at the PinchukArtCentre, critiques pacifism as a privilege of those in safety, highlighting that in the realities of war in Ukraine, peace can only be achieved through the provision of weaponry. The central element of the work is a drone carrying the well-known symbol of the dove of peace, which cannot "fly" on its own. After the exhibition, the drone was donated to the Rubizh battalion for military use.

Maksym Khodak. 'Dove of Peace Emoji,' 2024. Photo by Sergey Illin

An essential act of resistance has also been the practices of collective care, through which the artistic community redirected its efforts to support vulnerable groups in urgent need of assistance. Such acts of care were evident in Kharkiv, where artist Mykola Kolomiets from the children's art studio Aza Nizi Maza conducted workshops with children in a metro station. At the beginning of russia's full-scale invasion, the Kharkiv metro became a bomb shelter where people lived. In Lviv, a volunteer initiative called Kukhnia (Kitchen) was established and overseen by artists. They prepared hot meals for refugees at the train station and managed several shelters.

Artists Katya Libkind and Stanislav Turina also focused on supporting vulnerable communities. They provided assistance to a psychiatric hospital that, due to the war, urgently required supplies of medicine and hygiene products, as well as care and recreational activities for its patients. Notably, artists often choose to become soldiers or paramedics. Currently, it is difficult to discuss specific figures, including the number of those who have died, as these numbers continue to rise.

Every day, the sense of loss grows larger, proportional to the pain within each of us. The constant effort to overcome it and to keep moving forward has become a collective obligation, as has the memory of the crimes committed and the lives lost. As a former prisoner of war, soldier, and activist Maksym Butkevych, recently released after two years in russian captivity, noted in an interview: "The propagandistic version of history from the occupiers is now etched into my skin. It's a beautiful metaphor but not a very pleasant procedure." 18 Butkevych shared this while recounting his beating in a prison cell, where a guard forced detainees to recite Vladimir Putin's historical narrative. For every mistake, the activist was struck with a stick. These stories represent possible scenarios of a future that once seemed unimaginable. A future that has now become the present for the art center on Svitlyi Shliakh Street in Donetsk.

Reflecting on why art does not dissolve in the whirlwind of violence and continues to exist, I think that perhaps the answer lies in its ability to accumulate connections and build communities—linking and uniting, in opposition to violence, which can only destroy and create new voids. Art, therefore, cleverly invents practices to overcome pain and brings life back to places where it seemed to have vanished forever. It has the capacity to "reclaim territory from war," as critic and curator Borys Filonenko aptly described the process of rebuilding de-occupied territories through self-organized initiatives.

This is why a glimmer of hope still lingers within me: that one day, a minibus will once again take me to Svitlyi Shliakh Street, where, in the hangars of the Izolyatsia factory in Donetsk, I will once again encounter art, and my heart will beat a little faster.

Footnotes

- 1Rus, K. (2015, March 17). WWII Tank-Monument "Joseph Stalin" from Konstantinovka became the First Tank of Novorossia. Fortruss. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20150320062156/http://fortruss.blogspot.com/2015/03/wwii-tank-monument-joseph-stalin-from.html

- 2ІЗОЛЯЦІЯ. (2014). Press Release for the One-Day Exhibition of the Foundation

- 3Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2020). Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine, 16 November 2019 – 15 February 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/UA/29thReportUkraine_UA.pdf

- 4Ibid.

- 5Асєєв, С. (2020). Світлий шлях: історія одного концтабору. Quote from: Станіслав Асєєв. Реальна історія автора, який пройшов концтабір «Ізоляція». Laboratory. (2023, July 4). https://laboratory.ua/blog/realna-istoriya-avtora-yakyj-projshov-kontstabir-izolyatsiya

- 6NKVD (The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) was the Soviet secret police agency from 1934 to 1946 –– Editors Note

- 7Steyerl, H. (2016). A tank on a pedestal: Museums in an age of planetary civil war. e-flux Journal, 70. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/70/60543/a-tank-on-a-pedestal-museums-in-an-age-of-planetary-civil-war/

- 8IZOLYATSIA Factory. (n.d.). https://izolyatsia.org/static/izo-research/

- 9Aseyev, S., & Umland, A. (2020). "Isolation": Donetsk's torture prison. Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/donetsks-isolation-torture-prison/

- 10Media Initiative for Human Rights. (2020, February 24). Fear and Death in "Izolyatsia": How People Are Tortured in Donetsk's Basements. Ukrainska Pravda. https://web.archive.org/web/20200818215534/https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2020/02/24/7241046/

- 11IZOLYATSIA. (n.d.). Make up... Peace! Factory. https://izolyatsia.ui.org.ua/en/lipstick

- 12IZOLYATSIA Collection. (n.d.). https://izolyatsia.org/ua/collection/

- 13Kulikovska, M. (2012–2014). Homo Bulla – Human as Soap Bubble (Artwork). Donetsk, Ukraine. https://www.mariakulikovska.net/

- 14Kulikovska, M. (2010 – 2014). Army of Clones (Artwork). Donetsk, Ukraine. https://www.mariakulikovska.net/project-page/army-of-clones

- 15IZOLYATSIA. (n.d.). Make up... Peace! Factory. https://izolyatsia.ui.org.ua/en/lipstick

- 16Iakovlenko, K. (2023). From postmodern art to Stalinism: Donetsk's culture reimagined. Nationalities Papers, First View, PP. 1–10.

- 17Zhukova, N. (2023, February 9). 1 Million Euros Instead of Soledar's Culture Went to IDPs: How IZOLYATSIA Has Changed and What the Foundation Is Doing Now. Vilne Radio https://freeradio.com.ua/1-mln-ievro-zamist-kultury-soledara-pishov-na-pereselentsiv-zvidty-iak-zminylasia-izoliatsiia-ta-shcho-zaraz-robyt-fond-foto/

- 18Tatiana Kozak (2024, November 26). 'Putin's version of the history of Ukraine is left on me as a scar on my shoulder'. Maksym Butkevych on captivity, trial and release. Graty. https://graty.me/monologue/versiya-putina-istori%D1%97-ukra%D1%97ni-na-meni-zalishena-u-viglyadi-shramu-na-plechi-na-vse-mo%D1%94-zhittya-maksim-butkevich-pro-polon-sudilishhe-ta-zvilnennya/