Economies of the Aftermath

The Impossibility of Reconstruction and Fragmentation

The conventional approach to studying the aftermath of mass violence often rests on the assumption that reconstruction and reassembly are possible—like piecing together a fragmented puzzle—to restore a complete picture. However, as Yael Navaro recommends, the starting point must instead be the acknowledgment of the fundamental impossibility of research in the wake of annihilative violence. 1 This condition necessitates an awkward positioning of conceptual frameworks, methodological practices, and knowledge production within the very gaps left in the violence's wake.

We find ourselves confronted with a situation where the past has been rendered irretrievable, and the very foundations of research have been compromised. Rather than presuming the availability of evidence, we must reckon with its erasure, denial, misappropriation, inaccessibility, or irretrievability within the sites affected by mass atrocity. 2

In his seminal "Theses on the Philosophy of History," Walter Benjamin outlined an approach to engaging with the past when faced with the detritus of violence. Instead of attempting to reassemble the shattered fragments into a coherent whole or reconstruct the world that preceded the violence, Benjamin turned to the very remnants themselves as the conceptual apparatus, treating each component as an irreducible fragment of a puzzle that can never be fully restored. This perspective recognizes that knowledge of the past shaped by mass violence can only be accessed and represented in a fragmented, piecemeal manner. 3

Absence, Debris, and Negative Archaeology

This line of inquiry inevitably leads to questions about the role of the medium through which we might access the temporal context of the atrocities. As Marc Nichanian (2002) notes, "we are talking, after all, about nonexistent archives, about the nothingness of the archive." 4 From this starting point, we can further explore how to study that which has been intentionally buried from political discourse, systematically erased from the material environment, or transformed through misappropriation and denial.

Severin Fowles (2010) proposed the concept of "a negative archaeology," 5 which involves inferring from the absence of objects or categories within the archaeological record. As Mikkel Bille et al. (2010b) observe, "the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." 6 This underscores the importance of remaining attentive to absent material and conceptual spaces, especially when they have been actively made absent. Studying through the debris, as Ann Laura Stoler (2013) describes, is a "negative method" 7 that has been developed for engaging with the aftermath of mass violence, tracking "the uneven temporal sedimentations" in which imperial formations leave their marks and shape the psychic and material spaces of those who inhabit them. Ruins, in this context, are both physical manifestations and metaphorical representations of the ongoing legacies of colonialism.

Negative Archaeology of Economic Life

To study the economy in the aftermath of violence is to see it as a negative archeology of social activity, contours of human practices in the colonial condition—a fragmented, residual domain where the dynamics of production, exchange, and survival play out amidst destruction. Here, the economy cannot be abstracted from the conditions of annihilation that define it. Instead, it emerges as an architecture of gaps: disrupted labor, fractured market, and severed infrastructures. The remnants of economic life in war-torn cities are not merely debris; they are traces of negotiation, fraught with the weight of loss and the labor of enduring.

To reject the sanitized optics of classical economic systems that assume intact markets or coherent structures, instead study the economy through its absences and traces that are left in the aftermath—quiet markets, bombed production lines, evacuated spaces of labor, and improvised places of exchange. Following Stoler's concept of "imperial debris" (2013), the economy in such contexts must be read as shaped by the immediate exigencies of war yet tethered to enduring necropolitical goals that govern the lives caught within its structures.

In urban warfare, economic activity becomes an exercise in precarity. Labor becomes improvisational, prices oscillate wildly, and systems of exchange adapt to new, violent contexts. To understand such economies, one must move beyond the formal study of flows and figures, attending instead to the situated, embodied experiences of those navigating the ruin. It is within these localized acts—of bartering, scavenging, or surviving—that the fabric of an economic system reveals itself as a tapestry of resilience and loss.

Let's consider the economy in a lived space of ruin as fragments, where the absence of conventional structures forces attention to the improvisational and emergent. Focusing on the labor and transactions of individuals inhabiting these conditions, is an attempt to trace the contours of an economy marked by gaps and governed by necropolitical imperatives within occupational infrastructures. The infrastructure here is not merely seen as estranged or dysfunctional but as inhabited, adapted, and contested in the midst of its collapse. The next part is dedicated to the improvised structures for the exchange of goods and services that were formed in the conditions of ruination, and the way they are gradually replaced with built networks governed by occupational forces.

Case Study: Economic Ruin in Mariupol

Initial Responses to War

At 05:00 on February 24, 2022, Mariupol shuddered from cannonade. The sky over the Left Bank glowed red as sirens wailed, their howl strangely interrupted by pop music. The city's residents' immediate response revealed how eight years of hybrid war had shaped their economic reflexes—they went to work. Factory buses collected workers as usual, heading to the steel plants that had long served as islands of stability. "No matter what happens, steel is made," was the unspoken rule until management at both the Ilyich Plant and Azovstal suspended production, first as a "hot stop" allowing quick restart, then permanently as the reality of war set in. 8

The dissolution of normal economic life rippled outward rapidly. As Ksenia Safronova, a Mariupol resident, recounts, "When I went to the store on February 24, my mother said, 'Take a pack of pasta, a pack of buckwheat, and a kilogram of potatoes; we have everything else.' But the shelves were empty everywhere—and this was at noon! I also couldn't withdraw cash." 9 ATMs ran dry as residents rushed to secure basic necessities. When flour imports ceased, authorities were forced to negotiate with shop owners to control prices.

Photo taken from Telegram Channel, showing the limit on selling of bread

In these early days, efforts to maintain economic stability revealed both infrastructural fragility and human resourcefulness. Serhiy Marchuk, Head of Mariupol City Property Department, describes how, when commercial bread production faltered, "We received 100 tons of grain at the port and transported it to a grain elevator that hadn't been operational for three years... With the help of 20 workers from the plant and local volunteers, the flour was carried in shifts day and night until power outages stopped production." 10

By February 26, the formal economy began to disintegrate entirely. The Mariupol Chronicles documents how rumors spread that management had abandoned the Metro and PortCity shopping centers, leaving them open. When looting began, police fired warning shots, threatening to shoot under martial law. But they couldn't maintain a constant presence at every location. Marko Boyko, a 21-year-old student who spent 20 days in the city, observed: "By March 3, supermarkets were closed, and queues of up to 300 people formed at the only functioning store. When we ventured outside, we saw people looting stores—not just food but also electronics and furniture." 11

Photo from Telegram Channel, showing empty shelves in the supermarket

Disruption of Basic Services

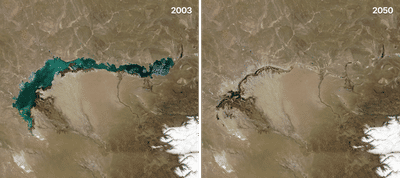

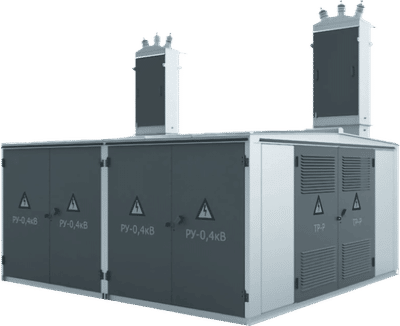

This collapse was not merely circumstantial—evidence compiled by Global Rights Compliance (2024) suggests it was systematically engineered. On February 28, Russian forces struck a powerline, plunging half of Mariupol into darkness. By March 2, all 15 electricity lines into the city had been destroyed. Konstantin Pismaryov, Director of Mariupol Energy Enterprises Department, described how "Russians systematically destroyed the city's power supply, targeting substations and knocking down power poles. On March 2, a critical substation north of Mariupol was damaged, and attempts to repair it failed due to ongoing shelling." 12

Satellite imagery revealed a deliberate pattern of infrastructure destruction. The city's power grid consisted of four principal substations: two 330-KV substations (Myrna-330 and Zoria-330), one 220-KV substation (Azovska-220), and at least 40 substations of 110-KV distributed across the city. The Global Rights Compliance SMJT investigation identified systematic damage to Myrna-330, Azovska-220, and at least 14 of the 110-KV substations—ranging from artillery craters to precision strikes on critical components. 13

Map of electricity infrastructure in Mariupol

Myrna 330 KV substation with signs of shelling on the buildings to the south of the site. Craters can be identified in the fields surrounding the substation. Google Earth Pro (c), Maxar, Image dated April 2022

The destruction of power infrastructure cascaded through other vital systems. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs had warned in 2019 that electricity cuts to Mariupol's water pumping stations could affect 474,000 residents. 14 This prediction proved devastating when the Starokrymskaya filtration stations lost power, cutting off access to potable water. As temperatures dropped to -12.4°C at night, the disabled electric pumps also meant no heating for residents.

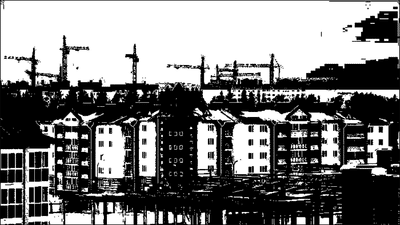

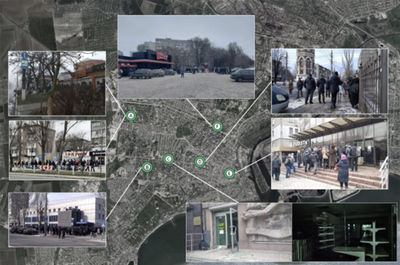

Emergence of Informal Economies

The disruption of normal economic life forced new forms of exchange to emerge. By early March, the Mariupol City Council had established "distribution points" for bread and essential items (Global Rights Compliance, 2024). However, these lifelines themselves became targets. Satellite imagery analyzed by the GRC SMJT shows that by March 14, at least three of the eleven announced bread distribution locations had sustained damage. Two more locations were hit between March 14-29, with the ATB supermarket on Karpinskoho Street apparently targeted twice.

Crater Beside Announced Bread Distribution Point – Google Earth Pro (c) Image Captured March 2022

Queues for Food at Distribution Points in Mariupol, Google Earth Pro (c), Maxar85

The attack on critical infrastructure followed a calculated sequence. Even before the full-scale invasion, on February 19, a transformer substation on the South Donbas Water Pipeline near Vasylivka was damaged, disrupting water supply to four filtration stations. The pipeline's location near the 2014 conflict frontline suggests pro-Russian forces were well aware of its strategic importance. When Mariupol switched to its backup water source—the Stary Krym Reservoir—this too was targeted through attacks on the Azovska-220 substation that powered its filtration stations.

Map Showing Location of Damaged Substation in Relation to the Water Pipeline Infrastructure Feeding Mariupol

Engineered Economic Collapse

The systematic dismantling of infrastructure created what one resident described as a "nothingness of basic services." 15 "There is no electricity, no water, no food in the city!" 16 recalls Kateryna, who attempted to maintain a small business in early March. Even cellular communications collapsed, with internet connectivity plummeting to seven percent of normal levels by March 2. As one Mariupol resident commented, "the light left us" —a phrase that captured both literal darkness and severed connections to the outside world.

Shelter itself became precarious. The Mariupol City Council's list of over 1,000 civilian shelters, mainly in building basements, became targets rather than sanctuaries. Global Rights Compliance documented systematic attacks on announced shelter locations, including Livoberezhnyi Palace, Molodizhnyi Palace, the Chaika Palace of Culture, and Art School No. 12.

Livoberezhnyi Palace after the attack. Image by Mariupol City Council

The destruction created a devastating cycle: as basic services failed, people were forced to venture out for essentials, exposing themselves to danger. Those seeking water faced particular risks. "Long queues formed wherever water was distributed by police or utilities," one resident reported, "but these gathering points became targets themselves." 17

This complete infrastructure collapse transformed everyday survival into a complex negotiation. Andriy Voytsekhovskyi, who eventually evacuated to Lviv, captures the paradox of this period: "You feel safe in a basement, but boarding a train traveling across a war-torn country feels very unsafe. Convincing my mother was the hardest part." 18 By March 5, those attempting to flee faced extortive prices, with desperate residents paying up to $500 or exchanging jewelry for transport to Melekino.

The destruction of basic infrastructure intersected with the systematic targeting of economic spaces. By mid-March, according to Global Rights Compliance (2024), Russian forces had damaged at least six supermarkets beyond those serving as distribution points. More significantly, the city's industrial backbone—the Azovstal and Ilyich steel plants that had provided economic stability for generations—became both shelter and battlefield.

The economic geography of the city transformed radically. Natalia, a North Mariupol resident who had moved there in 2014 from Snizhne, describes how military presence reshaped neighborhood economics: "On the night of February 28, I saw young Marines in blue tape urging us to wake neighbors and move deeper into the city as fighting approached. Days later, an officer asked for my bank card details, saying, 'We collected money; we're using your house and want to pay rent.' I cried and asked them just to survive." 19

In the absence of functioning banks, new informal economies emerged. The GRC SMJT documented how residents initially turned to barter systems, trading goods directly or exchanging jewelry and valuables for essential services. However, this improvised economy operated under increasingly desperate conditions. As one resident noted in local Telegram channels: "Everything has a price, but money has no value when there's nothing to buy." 20

Screenshot from Telegram channel, showing the introduction of dual-currency in the store

By early March, the city's economic life had fragmented into hyperlocal units centered around basements and shelters. Myroslava Nakhimova's account of 300 people organizing survival in a technical school basement exemplifies how these spaces became micro-economies: "Men guarded entrances during curfew, and others handled makeshift toilets or cooking. Children fell ill, and we shared what little medicine we had." 21 These shelter economies would later become the foundation for Russian occupation authorities to establish control through the selective provision of basic services.

The complete severing of supply chains created conditions that would later facilitate economic colonization. When Russian forces began offering food and basic services, they did so in a context where the population had been systematically deprived of alternatives. This strategy aligns with what Stoler (2013) describes as how "imperial formations leave their marks" 22 —not just through direct control but through the creation of dependencies in the aftermath of destruction.

The transition from destruction to occupation brought new forms of economic control. As Valentina, a retired resident who stayed in Mariupol, explains: "I had two apartments —one in a building overlooking the sea, the other in a historic building... The occupiers demolished the building overlooking the sea. Now in Mariupol, apartments are being given to Russians who come to work, or are sold. You can still take out a mortgage on the apartment that you had, then it was destroyed and now it is being rebuilt. This is nonsense!" 23

The reconstruction process became a tool of economic colonization. Property rights became contingent on forced naturalization 24—owners had to obtain Russian passports, and confirm ownership, all while keeping up utility payments on destroyed properties.

Screenshot from Telegram channel, showing the opportunities to work for a well-known Russian construction company tasked with reconstruction of Mariupol

Occupation and Economic Colonization

The occupation created a layered economic system where even basic services became tools of control. By May 2022, residents were paying for electricity access in an improvised economy of fuel trades: charging a phone for two hours cost one liter of A92 fuel, while charging a power bank for eight hours required four liters. This commodification of basic services, documented in local Telegram channels, reflected both the scarcity of resources and the emergence of new economic hierarchies.

Photo of a price list for electricity services: Charging a phone for 2 hours costs 1 liter of A92 fuel, charging a power bank for 8 hours costs 4 liters of A92 fuel, charging a flashlight for 8 hours costs 4 liters of A92 fuel, and charging machinery with an accumulator costs 1 liter every two hours of A92 fuel; 1 liter of of A92 fuel is priced at 50 rubles/25 hryvnias

By December 2023, as reported by OPORA sources, the occupation regime had formalized its economic control through a "free economic zone" (FEZ) in the temporarily occupied territories. This seemingly developmental initiative masked a deeper process of resource extraction. According to the Center for National Resistance, the FEZ project, directly supervised by Russian Deputy Prime Minister Marat Khusnulin, served to redistribute financial flows to companies aligned with occupation authorities.

The transformation of business ownership followed a clear pattern. Local enterprises faced an impossible choice: re-register under Russian law or face "nationalization." Kateryna recounts how her friend's small shop operated in legal limbo: "They did not register it with Russian state services: 'So as not to reveal the information about her husband, because they would start receiving summonses.'" 25 Meanwhile, larger enterprises were systematically appropriated through what occupation authorities called "external management."

Screenshot from Internet Archive, showing a transition of a domain name from 'tov', coming from Ukrainian ТОВ to Russian OOO

The occupation economy became stratified among clear winners and losers. As one Mariupol volunteer notes, "builders, money changers and transporters" prospered while local businesses struggled. 26 The financial system itself became a tool of control—while transactions were conducted in rubles, people could still transfer hryvnia to relatives on Ukrainian cards, creating a parallel economy of currency exchange that benefited occupation-aligned "money changers."

The economic transformation of Mariupol reflects broader Russian strategies in occupied territories. By 2024, according to budget "legislation" documents, Russia allocated over 430 billion rubles to the occupied territories, with specific distributions: 137.4 billion to Donetsk region, 126.7 billion to Crimea, 92.5 billion to Luhansk, 60.1 billion to Zaporizhzhia, and 33.2 billion to Kherson. However, this apparent investment masks a deeper process of economic extraction. 27

The occupied territories have become deeply subsidized regions that paradoxically generate wealth for specific actors. As one source from OPORA explains, "The general logic of the occupiers is simple: they want to take as many resources as possible out of the territory of Ukraine, but at the same time they are interested in launching enterprises that can work for the war." These include logistics companies, concrete manufacturers, and military equipment repair facilities. 28

The transformation is perhaps most visible in the construction sector. Russian propaganda channels showcase restored building facades while hiding the reality described by local residents. As Inna observes, "Some houses in the city are being restored only from the outside—for the sake of the picture... Mariupol for Russians is a business project. Nobody thinks about the people or the history of the city." 29

Understanding Economies as Spaces of Absence and Control

This transformation of Mariupol's economy reveals how studying the aftermath of mass violence requires attention to both absences and emergent forms of control. Following Stoler's concept of "imperial debris," we see how the systematic destruction of infrastructure created conditions for new forms of economic colonization. The remnants of economic life are not merely debris but, as demonstrated through personal testimonies and documentary evidence, are sites where the dynamics of survival, resistance, and exploitation continue to play out.

The occupied city's economy now exists in what appears at first glance to be a paradox: deeply subsidized yet generating wealth, "reconstructed" yet dispossessing original residents, "free" yet tightly controlled. However, this paradox dissolves when viewed through the lens of colonial economic logic. The very gaps created by systematic destruction—in infrastructure, property rights, and economic networks—have become spaces where new forms of dependency are engineered.

Today's Mariupol embodies what Fowles terms "negative archaeology"—where the absence of previous economic structures reveals as much as what remains. In evacuated spaces of labor, destroyed markets, and severed supply chains, we find not simply destruction but the contours of new imperial formations. The transition of business registrations from Ukrainian TOV to Russian OOO, the implementation of dual currencies, and the selective provision of basic services all represent not just changes in economic administration but fundamental transformations in how value is extracted and control is maintained.

This study suggests that understanding economies in the aftermath of mass violence requires attention not just to what has been destroyed, but to how destruction itself becomes a tool of economic colonization. In Mariupol, we see how the economy cannot be abstracted from the conditions of annihilation that define it. Instead, it emerges as an architecture of gaps—disrupted labor, fractured markets, and severed infrastructures—where the dynamics of survival and exploitation continue to evolve.

The fragments of economic life in Mariupol—from informal currency exchanges to selective reconstruction projects—reveal not just the weight of loss but the ongoing labor of both enduring and resisting new forms of economic control. In studying these fragments, we uncover not a complete picture, but rather, as Benjamin suggests, fragments of violence that can never be fully reassembled, yet must be understood in terms of their ongoing impact on human lives and communities.

Footnotes

- 1Navaro, Y. (2020). The aftermath of mass violence: A negative methodology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 49, 161–173.

- 2Ibid

- 3Benjamin, W. (1978). Theses on the philosophy of history. In Illuminations. H. Zohn, Trans., pp. 255-266.

- 4Nichanian, M. (2002). Writers of disaster: Armenian literature in the twentieth century. pp. 13–14.

- 5Bille, M., Hastrup, F., & Sørensen, T. F. (2010). Introduction: An anthropology of absence. In An anthropology of absence: Materializations of transcendence and loss. P. 11.

- 6Ibid P. 11.

- 7Stoler, A. L. (2013). Imperial debris: On ruins and ruination. Duke University Press. P. ix.

- 8Texty.org.ua. (2023). Mariupol chronicles: A city at war. Retrieved from https://texty.org.ua/d/2023/mariupol_chronicles/

- 9Retrieved from https://www.m86.city

- 10Ibid

- 11Ibid

- 12Ibid

- 13Global Rights Compliance (2024). The Hope Left Us: Russia's Siege, Starvation, and Capture of Mariupol City. Research Report, 2024. PP.16-17

- 14General Coordination Meeting – Mariupol, Ukraine, OCHA (11 April 2019), available at: https://web.archive.org/ web/20230920021420/https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/ files/gcm_mariupol_20190411.pdf

- 15Retrieved from https://www.m86.city

- 16Suspilne.media. (2024). Life hasn't stopped, but it's life in constant fear: Mariupol residents on everyday life under occupation. Retrieved from https://suspilne.media/747837-zitta-ne-zupinilosa-ale-ce-zitta-v-postijnomu-strahu-meskanci-mariupola-pro-budni-v-okupacii/

- 17Retrieved from https://www.m86.city

- 18Ibid

- 19Ibid

- 20Retrieved from local Telegram Channels.

- 21Retrieved from https://www.m86.city

- 22Stoler, A. L. (2013). Imperial debris: On ruins and ruination. Duke University Press. P.2

- 23Suspilne.media. (2023). Life of Mariupol under occupation: A story in social media posts. Retrieved fromhttps://suspilne.media/306408-zitta-mariupola-pid-okupacieu-istoria-v-postah-z-socmerez-ta-povidomlennah-z-budinkovih-cativ/

- 24U.S. Department of State. (2023). Forced naturalization of Ukrainian citizens in Russia-occupied areas of Ukraine. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/briefings-foreign-press-centers/forced-naturalization-of-ukrainian-citizens

- 25LB.ua. (2024, February 14). Occupied: How Russia squeezes the economy. Retrieved from https://lb.ua/news/2024/02/14/598170_okupovani_yak_rosiya_vidzhimaie.html

- 26Ibid

- 27LB.ua. (2023, January 6). Russians export Ukrainian grain. Retrieved from https://lb.ua/society/2023/01/06/541625_rosiyani_vivozyat_ukrainski_zerno.html

- 28Ibid

- 29Suspilne.media. (2024). Life hasn't stopped, but it's life in constant fear: Mariupol residents on everyday life under occupation. Retrieved from https://suspilne.media/747837-zitta-ne-zupinilosa-ale-ce-zitta-v-postijnomu-strahu-meskanci-mariupola-pro-budni-v-okupacii/