System of Dependency: "Druzhba" project.

Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas in conversation with Tatiana Kochubinska

This conversation reflects on the artistic project "Druzhba" by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas that the artists have been developing since 2003. The project explores the political, economic, and cultural implications of the "Druzhba" pipeline, examining the geopolitical and infrastructural legacies of the Soviet Union, as well as the political power and privatization that followed its collapse. Through the conversation, together with the artists we uncover the historical, political, and social layers embedded in the pipeline's operation, expressed through the art installation of the same name, which blends themes of infrastructure, power, and the irrational and magic.

Tatiana Kochubinska: To begin, could you describe the context in which your "Druzhba" project originated? How did it start, and how has it evolved over the years? How have shifting political landscapes and revolutionary changes influenced your work and its representation?

Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas: It makes sense to start from this question. Well, our generation lived through all these changes. As the movement for independence was forming, and we were students at the Vilnius Academy of the Arts, we took part in student strikes pushing for changes in the school and university. We managed to change the leadership, and professors who collaborated with the regime had to leave. It's interesting that in Lithuania, the independence movement began with intellectuals—musicians, artists, writers—and students were very political.

Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas in front of their installation 'Druzhba', 'Borders Are Nocturnal Animals' exhibition, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2024, Photo by @saisonlituanie2024, Courtesy of the Artists

As a result, one system was replaced by another, and these rapid changes, brought about by neoliberal capitalism and the privatization of the commons, had a huge impact on society. In our artistic work, we focused on the effects of these rapid transformations, approaching them from various perspectives. One of our efforts was running an artist-run independent organization, which we established in 1993—perhaps the first of its kind in the country and in the Baltics. We also started working on research-based projects. These projects had an interdisciplinary and critical character, reflecting on what was happening in society. Our first breakthrough project, Transaction, involved psychiatrists, women intellectuals, and film archives. Exactly through the film archives, we became involved in reflecting on privatization, as the film studio and archives themselves were privatized. Suddenly, we were witnessing not only the demolition of buildings for real estate speculation but the disappearance of actual archives as documents of memory, which were ending up in the hands of real estate developers. These were the paradoxes of the time, like wild turmoil of that time marked with a kind of phantasmagoric irrationality.

That's how we also came across the privatization of the major infrastructure, like Mažeikiai refinery, which is the pipeline's "Druzhba" end in Lithuania. We started to think about the infrastructures that are invisible, like pipelines, which only become visible when something goes wrong.

T. K.: And how did the artistic project "Druzhba" come about and how was it shaped?

N. & G. U.: The project started in 2002 at the artistic residency in Schloss Solitude 1 in Stuttgart. Jean Baptiste Joly, the founding director of the Akademie Schloss Solitude, started a new program within the residency where he invited artists, business people and scientists to work together, suggesting to investigate the concept of the network. This conversation was influenced by theorists like Bruno Latour and Manuel Castells. The reflection at the time focused on large financial networks and the ideas that emerged in the 1990s, such as the "end of history" and the dominance of global capitalism. The dot-com crash in 2001 raised questions about the network itself. "Network" became the buzzword—it had entered the vocabulary and quickly became a trendy, even fashionable, term.

Within this context we suggested other artists and scientists at the table to investigate "Druzhba" infrastructure as an example of the network.

'Druzhba' installation view, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, Germany, 2003, Photo by Nomeda Urbonas, Courtesy of the Artists

T. K.: In this initial phase, did you approach "Druzhba" as an ideological concept, or did you focus on the pipeline itself from the beginning?

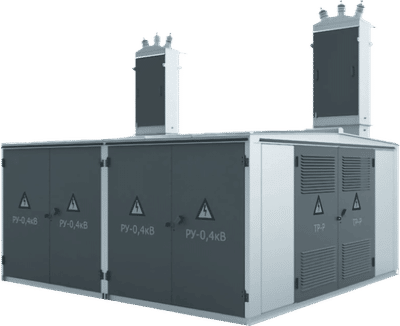

N. & G. U.: A pipeline, you know, it's always a play of words. We introduced the map of "Druzhba" as a network that connects various geographical locations and independent countries. Unlike an Internet network or a network of friends, this network of pipes is very material, and not elusive; it is one of the largest networks in the world; it is a system of refineries, pumping stations and automated control centers. While it connects for specific purposes, much like how software systems link accounts, its physicality and infrastructure make it fundamentally different. This network isn't new—it has existed for 50 or 60 years, connecting generations of people. Their lives and bodies are intertwined with it, whether as experts, service personnel, administrative workers, or others involved in its operation. Over time, an entire workforce has been dedicated to maintaining this network, while entire countries, in some ways, have become enslaved by it.

We proposed examining the network from multiple perspectives—financial, cybernetic, representational, narrative, and cultural—seeking to understand and engage with it in different ways. This framework essentially laid the foundation for how the project began. Research-based art in a way was a counter-reaction to modernist and very formal or traditional art forms that characterized the period before these changes. This practice reflected the new times and the possibilities they brought. Research, in this context, became our instrument, tool, and methodology.

T. K.: From today's perspective, the "Druzhba" pipeline seems to be a huge infrastructure of power. In the context of the early 2000s, when you worked with experts from various fields, what was the response to the pipeline as an active infrastructure (which is still active today)?

N. & G. U.: Back then, in 2002, "Druzhba" was actually in the hands of "Yukos" 2 company, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who at that time, was the richest man in the world. Back then he had an ambition to outsource Siberian oil to Americans, negotiated with Japan, China etc. In our project, we were reflecting from two perspectives: on one hand, privatization and the networks of financial and political power. On the other hand, there's the inherent contradiction, as power cannot force genuine friendship. As someone once said, you can't be told to be friends. This paradox is built into the proposition itself. So, in "Solitude" with this transitory group of people around the table, we agreed that the project had many facets. We needed diverse expertise to fully engage with it and navigate its complexities. For example, there was a Hungarian writer Peter Zilahy, with whom we started to write a script and who spoke Hungarian. At the time, we naively thought we would go to Siberia, visit the oil fields, and talk to the local tribes. Their language was linked to Finno-Ugric, so we hoped we might even understand each other. We had read articles about how the company had essentially colonized these vast fields with the land and with the people who live there.

'Druzhba' installation detail, 12th Kaunas Biennial, Lithuania, 2019, Photo by Nomeda Urbonas, Courtesy of the Artists

We knew Druzhba pipeline's endpoints run into Ukraine, Belarus, Slovakia, and the Adriatic. Later, we learned that it passes through Germany, continues into France and extends even to Marseille. These pipelines are interconnected into one system, providing oil to much of Europe. Though the branches are named differently by the companies that own them, they all form part of the same Druzhba network.

For many people around the table, this was completely new. At the time, the post-colonial discourse often focused on the imperial histories of Britain, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy, but Russia as an empire was largely absent from that conversation.

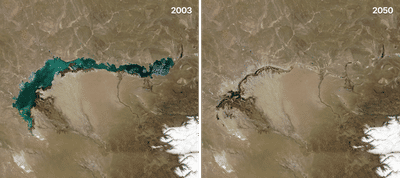

The pipeline was built in the 1960s, and now [2003, when the first installation was created — Author's note], 40 years later, we realized we are dealing with Druzhba's legacy. It has such an enormous capacity as economic and political power, so it can dismantle governments or destabilize entire states. It's not just physical; as we said, there are also metaphysical aspects to it—something that touches your unconscious. We began looking at different films and cultural phenomena that fueled modernity, particularly the idea of endless access to energy.

T. K.: At what point did your focus shift from just the economic side of things to considering the decolonial perspective? How did you start looking at the ideological and cultural impacts, especially in terms of how Soviet infrastructure affected people's lives and power dynamics?

N. & G. U.: It wasn't like we were studying something and then came to terms within it. We were witnessing disintegration of infrastructure as it was happening, especially with privatization and certain decisions made by different parties, groups and governments. Privatization was a key project in the early 1990s, marking the beginning of a new era. We —in Lithuania— were entering negotiations becoming part of NATO and the EU, and moving toward the Eurozone. To prove that we were accepting privatization, we had to show we were running a liberal democracy based on the free market. Privatization became the proof of political readiness. At the same time, we saw how public property, the major driver of the economy, was being transferred to private hands.

We watched as the state-run refinery in Lithuania (the biggest of its kind in Eastern Europe) was sold to an American company, then quickly sold again to a Russian company, and later run by Yukos. As we dug deeper, we realized that this was no longer about the nation-state. We began to look at the "Druzhba" pipeline from a "hyperobject" perspective —beyond borders, agreements, and democratic systems— while also delving into archives. We became deeply interested in the moment when Soviet modernity began to override local ecosystems. On one hand, you had the modernity introduced by the United States with the Marshall Plan after World War II, bringing design, media and film that shaped the image of modern life in Europe. We looked at the effect produced, including in the Soviet Union, with the American exhibition in Moscow. In different projects, we explored these aspects, but the starting point for us was the energy project, which we saw as the ultimate realization of modernity. It was a forceful transformation of entire cultures, offering a promise of friendship while brutally reshaping landscapes, building settlements, and laying down pipes. This was, in a sense, a social and cultural engineering project. At the same time, we were aware of the hidden world of energy that powered it all.

T. K.: And how did you translate your conceptual thinking into visual form, how did you structure it in order to convey your ideas artistically?

N. & G. U.: In 2003, by the end of the Art, Science & Business residency at Akademie Solitude, we were asked to present the research as an exhibition in one of the project rooms of the castle. We structured the material in the form of a diary, like a "Druzhba" storyboard. As a journey, traveling along the pipeline, the narrative navigates through three layers: one would be of the media references and art, another would be a real (hi)story of the "Druzhba", and the third one would be a magic —signs, symbols and weird things occuring along the pipeline. We were compelled to explore tensions between the physical and metaphysical, between political power over marginalized people and these people's stories.

'Druzhba' installation view, 'Borders Are Nocturnal Animals' exhibition, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2024, Photo by @saisonlituanie2024, Courtesy of the Artists

For example, we met Ivan Dolozczynskyi, a Ukrainian who lived in Biržai and who witnessed how the pipeline was built. His whole life was dedicated to this pipeline project, thus his voice has given us a worker's perspective. From Ivan we learned how through privatization people who worked for the pipeline were pushed to the margins. In addition we get interested in the metaphysical energy, and start looking into where a resistance to modernity is.

For example, the shamans living on the oil fields, in territory surrounded by barbed wire. Company owning the pipeline comes with helicopters, dropping what they need—salt, gunpowder for hunting. It doesn't matter who is the owner, Yukos, Rosneft or Transneft, this colonial infrastructure reproduces its omnipotence.

This "hyperobject" functions regardless—war, government changes, political shifts—it continues to reproduce. That was a scary thought. So we started thinking about resistance. What could it be? We looked for inspiration: shamans, paganism, even madness. Trying to mirror back this extreme rationality that exceeds itself and becomes madness.

'Druzhba' installation view, '(re)Construction of Friendship' exhibition, KGB Museum, Riga, 2014, Photo by Mākslas telpa, Courtesy of the Artists

T. K.: It's an interesting thought—the double faces of rationality and madness. I just want to clarify a few things. You mentioned the diary and the three layers in the installation. If I understood correctly, you first presented this in Schloss Solitude. Where did you gather the archive, and how did you conduct the interviews? Was it just the starting point? Also, regarding the diary, you never actually traveled through the pipeline or its locations, right? You spoke to people in Lithuania?

N. & G. U.: This diary is our imaginary journey—semi-fictional. It's semi-fictional because we did research in Lithuania. Peter, the Hungarian writer, came with us, and we traveled along the pipeline in Lithuania—refineries, pumping stations, even a buoy in the Baltic Sea. We followed everything possible at that time.

We made contact with Yukos and met with their PR representative for Eastern Europe, to discuss the possibility for us to travel along the pipeline to the Siberian oil fields. We were preparing to travel, meet people working there, and start the film. Of course, we sensed the need to be careful with language, playing tricks to navigate the situation. During our meeting in a Vilnius café, the PR representative received a call. After the call he abruptly left. We never saw or heard from him again. That was the sign that the Kremlin had begun dismantling Yukos. When we arrived in Stuttgart for the installation of the first "Druzhba" presentation in September, Khodorkovsky had already been arrested by Putin. Our trip to Siberia never happened.

But in Lithuania we performed this trip along the pipeline's small branch. We visited factories, met workers, explored archives, and watched films about the refinery's opening, branch construction, and more. We gathered news—paper clippings, reports—exploring connections and conducting a kind of forensic investigation into this "body" that seemed both dead and alive.

T. K.: What defines the installation's form, and how does its evolving archive and collected media—like Soviet-era artifacts—reflect the project's ongoing dialogue with history and the constantly changing context of today?

N. & G. U.: In the first decade, our presentations took the form of a diary, including media archives, interviews, and collected materials organized as a cybernetic network. But in a way it was quite challenging to really grapple with that history. Among many documents in the archives we came across a Xerox copy of a map of 18th century Europe depicted as political satire, where countries are represented as exaggerated personifications and humorous metaphors. While there are many specific and funny details about Britain, Scotland, Spain, Scandinavia or Italy, Russia stands out as a wild monster figure with a bloody knife, threatening Europe. Essentially, nothing has changed.

So in our first presentations, we covered the entire space with architectural tracing paper, a material chosen for its association with blueprints and its ability to convey a sense of tracing and uncovering layers of history. Diaries, notes, images, newspaper clippings, and other archival materials were meticulously arranged in a designed layout, organized into chapters or layers. Tracing paper played a conceptual role, symbolizing the act of tracing disintegrating networks and bodies. This choice extended to the use of media images projected as slides through carousel machines, reflecting the fragmented and layered nature of the collected material. The slides showcased images from archives, including refineries, objects used in ceremonial openings, and monuments like large stones inscribed to mark infrastructural achievements—juxtaposing rational Soviet modernity with a psychedelic sense of irrationality.

'Druzhba' installation view, The Baltic Pavilion, 15th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Photo by Jonas Zukauskas, Courtesy of the Artists

The 2016 presentation of the "Druzhba" project at the Venice Architecture Biennale marked a significant shift in form. For the Baltic Pavilion, held in Palazzetto dello sport—a brutalist sport hall at Arsenale—our research was displayed on a black plastic surface—an industrial material used to contain toxic substances. This plastic formed a large "puddle of oil" that cascaded across the space, while its surface was layered with narratives, diaries, and images. The scale of the puddle emphasized the material and symbolic weight of the subject matter. Subsequent presentations adapted this concept to different spaces, recycling the black plastic and cutting it into smaller, splash-like shapes. These iterations explored the project's evolving relationship with the infrastructure and narratives it interrogates.

T. K.: The Druzhba pipeline, as you relate it, symbolizes power—it's both an infrastructure and a tool of control. Despite its history, it still functions and exerts influence. How do you envision the future of such infrastructures? Can we talk about the rebranding of control, considering that, as you mentioned, nothing has really changed?

G. U.: We're talking about the rebranding of control, but how can we envision the future of such infrastructures when they just keep growing new heads, like a dragon? It's a paradox inherent in every large infrastructure. We actually explored this through yet another project back in 2011, which looked into the "red telephone" hotline established after the Cuban missile crisis to connect White House and Kremlin. Our entry point into that story was in Finland, on Korpo Island, where we discovered a telecommunication bunker designed to reinforce the signal. Since Finland was a neutral state between these two superpowers, it served as a relay point, ensuring secure communication. The bunker was built in the 1960s, and decommissioned in 2006, but still stands as a testament to this ongoing infrastructure. Even though the cables were cut and dismantled, and new technologies were implemented, the bunker itself is impossible to fully dismantle unless it's really blown up. Since it's so massive, like bunkers along the coast in France, it remains forever. It is fascinating to realize it requires ongoing maintenance. As long as it remains a space where humans can enter, one has to create the conditions for secure life. So we call it the paradox of the bunker. Once it's built, it will always be a bunker.

I'm using this parallel to answer your question. Once the pipeline is built, it's impossible to dismantle it.

N. U.: The Baltic Pavilion also looked at the infrastructural scale—what happens with massive infrastructures that are not on a human scale, but are hyperobjects. It depends on the perspective we take. Looking from the deep time, these infrastructures might be taken over by other species, not humans, and perhaps not even the bats, as they most likely will be extinct by then. Something else will take over. Druzhba will disintegrate, and maybe the oil will be finished, leading to some kind of transition.

Otherwise, it would require a radical decision to dismantle the pipeline. But I don't see that happening for at least another 100 years. As long as it's there, it will always create phantoms.

G. U.: Frankly, I don't know if the energy transition will require such a radical political decision to dismantle the pipeline. As long as it's there, something else has to substitute it, because the demand for energy keeps growing. Energy is at the core of every civilization; the more developed a society becomes, the more energy it needs. In the end, we might destroy ourselves because of this inherent drive for energy.

I honestly don't have an answer. It's a hyperobject. Colonialism is also a hyperobject. If colonialism is a hyperobject and ungraspable, all we can do is enter and produce leaks in the system, and these leaks become apparent.

So, when we are asked how the work changes, how "Druzhba" installation changes over decades, with all the historical shifts taking place, the answer is, in a way, yes—we update it, but not significantly. The core story of a given time and scale remains the same, ongoing. But within the new context, we can make a leak, a new reflection of the moment. Even without fully comprehending the entire, incomprehensible thing, through that leak, we can create a new reading.

Perhaps it's an ongoing process. In a way, it's impossible to finish this work, which is why it remains in a constant search of its own form.

'Druzhba' installation view, 'If Disrupted, It Becomes Tangible: Infrastructures and Solidarities beyond the post-Soviet Condition' exhibition. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, 2023, Photo by Katsiaryna Miats, Courtesy of the Artists

Footnotes

- 1Akademie Schloss Solitude is an international and multi-disciplinary Artist-in-Residence" program in Stuttgart, Germany

- 2Yukos was a major Russian oil and gas company that was forcibly broken up and declared bankrupt after the arrest of its owner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, in 2003.