Editorial. Issue 1

The inaugural issue of the AWC Journal, entitled Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization, addresses how civilian infrastructures are co-opted, transformed, and often weaponized in a situation of modernity. In this edition, with authors from Belarus, Croatia, Kazakhstan, Lithuania, Ukraine, etc., we examine various forms of interaction between civilian and militarised infrastructures, especially those affected by war. From strategies of invisible incorporation and the mimicry of militaristic infrastructures in the leisure and entertainment industries to how intimate infrastructures evolve into structures of "slow violence," this issue also examines the connections between weaponized, colonized, and environmental terror and explores possible forms of resistance and solidarity.

The idea of the first issue is shaped mainly by the activities of the International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine—discussions, screenings, exhibitions, and artistic projects that emphasize the global interconnectedness of the world through people, communities, systems, places, infrastructures, and art. This is evident in a variety of video works presented on our digital platform.

Metasitu. States Status Statues and Statutes, 2016, 03:38 from antiwarcoalition.art

For example, Metasitu's collective States, Status, Statues and Statutes (2016), 1 which examines the resurgence of imperialist agendas through Moscow's VDNKh (Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy) 2. Initially established in 1935, the site was repurposed in the 2010s to 'revitalize' Soviet kinship narratives within a neoliberal framework. Here, market forces and imperial ideology merge into a militarized discourse of dominance and grandeur. Culture and museums, often perceived as neutral, function instead as ideological tools, reinforcing state narratives and shaping public perception.

Mladen Stilinović artwork at Biennale of Contemporary Art D-0 ARK, Konjic, 2015.Copyright © Sanjin Đumišić

We are used to representing the connections between culture, more particularly contemporary art, and militaristic infrastructures through the borrowing of vocabulary such as 'avant-garde,' 'curator,' and others, or a process of gentrification. For instance, contemporary art institutions ZKM in Karlsruhe and Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv were opened on the site of armoury plants. Another example is the D-0 ARK Biennial (Bosnia and Herzegovina), an event that takes place in the former place of the atomic fallout shelter built especially for Josip Broz Tito as well as the political and military elite of Yugoslavia. These militaristic spaces are now welcoming institutions for contemporary art that erase traces of the former militaristic presence in one way or another. However, is there a potentially reversible militarisation of cultural institutions that unfold on former military institutions? Or is this militaristic component embedded in the very structure of modernity as a constant threat of possible terror and repression? This reverse occupation of cultural institutions by structures of violence is a marker for understanding modernity. Thus, in Ukraine, civil infrastructures are being repurposed into infrastructures of survival, militarism, or even torture—a tragedy exemplified by the Donetsk platform for cultural initiatives, Izolyatsia. Natasha Chychasova discusses this in her powerful and thorough text Adaptive Violence: How War Transformed Institutions and Art, 3 exploring how art continues to exist and survive amidst war.

This is one of the most dramatic cases in the russian-Ukrainian war - the transformation of a contemporary art centre into torture prisons and the occupation of an international collection of contemporary art - shows how the aesthetic and the political are deeply intertwined. By returning to the idea of the AWC Journal, however, it also shows the role of art as an inside/out, that is, as both an assemblage of tools, tactics, and practices that help to reveal the militarisation of civilian infrastructures and at the same time, a place where this fusion of militaristic and civilian infrastructures takes place with a high degree of intensity. In this context, the artist and/or cultural worker appears as a figure of trickster who holds his or her speech as part of a process of violence, power dynamics, inclusion/exclusion, and simultaneously fragile corporeal existence. In this deliberately weak position, with a high probability of failure, the authors of the journal uncover and collect evidence of militarisation and violence incorporated into the very heart of our everyday lives while at the same time sketching possible strategies of resistance to the totality of militarist infrastructures.

Understanding Infrastructures

War is not isolated but rather affects and engages various geographies—both near and far—through specific infrastructures such as food distribution, the internet, cheap labor markets, knowledge production, the IT industry, land and sea networks, and more. As Patrick Wolfe pointed out, "invasion is a structure, not an event," 4 focusing on an infrastructural understanding as a branching structure where different types of violence are interconnected and perpetuate each other. Notably, the term 'infrastructure' has militaristic origins, emerging post-World War I to describe logistical networks supporting armed forces.

Infrastructures are often perceived as the unseen foundation of our daily lives, yet their presence is deeply political. They are not merely technological systems but relational networks that facilitate movement and create the opportunity for the operation of other objects, institutions, and structures. He describes infrastructures as "matter that enables the movement of other matter... they are things and also the relation between things." 5 This perspective highlights the dual nature of infrastructures: They are both material and relational, constantly influencing social, economic, and political structures.

Sense of Safety. Expanded exhibition as part of Bridges of Solidarity at ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany, Installation view featuring Children's Game # 39: Parol (2023) by Francis Alÿs, video installation and work adaptation: Maxim Tyminko, © ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, photo: Karolina Sobel

Moreover, infrastructures are deeply entangled with economic systems that exploit both human and non-human resources, making them central to understanding labor struggles and environmental destruction. Infrastructures shape economic dependencies, 6 governance, and ecological devastation, highlighting the inseparability of economic and infrastructural processes. Infrastructures should be viewed not just as physical networks but as socio-technical systems that mediate power through algorithms, data flows, and surveillance.

On the one hand, infrastructures have a branched structure that includes not only institutions and relations between them but also affects, ideologies, etc. On the other hand, modernity fuses knowledge production and militaristic discourse, advances in technology, strategic design, and operational efficiency. 7 Therefore, how knowledge production processes are drawn into war is a litmus test. For instance, the Kharkiv Institute of Scintillation Materials products are used to develop a new Hadron collider. For us, this demonstrated the deeply intertwined nature of the world, highlighted, unfortunately, through war. Scientists at the institute repurposed infrastructure originally intended for innovation to meet everyday needs while continuing their research. This is documented in a series of photographs, Shelter for Science 8 (2022) by Oleksandr Osipov, featured on our digital platform. In our issue, the series is brought together with Maryna Konieva's essay, Community, Science, and Art: Mutual Support in Times of War, 9 where she examines how the Institute's workers blend scientific resilience, community survival, and the rescue of Ukrainian cultural heritage under extreme conditions of war.

It is essential to locate the Infrastructures within imperial and militarized frameworks, showing how logistical networks, pipelines, and global supply chains are embedded in histories of colonialism and military occupation. Infrastructures are sites of contestation, where power struggles over land, mobility, and sovereignty unfold. 10 So, the entanglement between infrastructures and military operations, particularly in the sense that infrastructure can serve civilian and military interests, blurs the lines between the two.

The etymology of "infrastructure" itself underscores its invisibility—the Latin prefix infra- means "underneath"—suggesting that military infrastructures often blend seamlessly with civilian ones, creating blind spots where militarization remains unnoticed. Antonia Dika's Military on the Coast in Times of Peace 11 examines how Yugoslavia's Cold War coastal defenses coexisted with the booming tourism industry despite being absent from planning documents. Underground bunkers, missile systems, and barracks were concealed within natural landscapes, allowing tourists to unknowingly interact with militarized spaces—swimming near naval zones or skiing past defense sites. Once the Yugoslav state dissolved, these hidden infrastructures emerged as visible ruins, relics of a once-powerful military apparatus now left to decay.

Sense of Safety. Expanded exhibition as part of Bridges of Solidarity at ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany, Installation view featuring Permanent Vacation (2023) by Mark Požlep, video installation and work adaptation: Maxim Tyminko, © ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, photo: Karolina Sobel

This statement becomes central to the AWC Journal. As explored throughout this issue, infrastructures are weaponized during conflicts, transforming civilian networks into strategic assets. The militarization of infrastructures—from energy grids to digital platforms—disrupts everyday life while enabling control over populations and resources.

Militarization Across Spheres

As in the case of the Adriatic coast in Yugoslavia, militaristic infrastructures can be created in the shadows, parallel to the tourist infrastructure, continuing the well-known logic that if you want to hide something, put it in a public place. The crowdedness of the recreation system made the militarist system invisible and unremarkable. However, militarisation can not only exist alongside civilian infrastructures but also take over them, penetrating the most seemingly distant spheres from war –– intimate and everyday use, turning our notions of terror upside down. In such a situation, the object of violence is not just a subject but a spectrum of agents from human to non-human.

Environmental Terror

Environmental destruction is a crucial dimension of militarized infrastructures, affecting both human and non-human agents. Process as vertical occupation, arguing that war does not end with territorial de-occupation but continues through long-term ecological devastation. 12 Authors of the AWC Journal highlight how war extends beyond the battlefield, embedding itself into landscapes, waters, and air, transforming entire ecosystems into sites of slow violence. Liza Goncharenko's The Weaponization of Ecosystems 13 further explores how war transforms nature into a battlefield. "The war does not only target bodies; it targets soil, water, and air," 14 she writes, highlighting how military tactics include flooding territories, poisoning water sources, and systematically destroying agricultural lands.

For instance, in her article Revealing the Landscape: Mapping Cyclical History of Colonial Infrastructure of the Kakhovka Dam, 15 Sonya Isupova engages in an artistic investigation of how colonial infrastructural legacies, particularly hydroelectric projects, continue to shape environmental destruction in the case of Kakhovka Dam, which was breached on June 6, 2023, by russian troops. Many researchers and human rights activists recognise the bombing of the Kakhovka Dam as ecocide. 16 Sonya Isupova combines forensic mapping, machine-generated cartographies, and the artistic approach to reconstruct the transformation of the landscape over time. Using a custom-built mapping machine, Isupova explores how technology can be repurposed for counter-cartography, uncovering hidden layers of ecological damage. In her visual essay, the artist uncovers the environmental impact of the Kakhovka Dam's destruction, highlighting colonial dependencies, infrastructure militarization, and the role of both human and non-human agents in environmental terror.

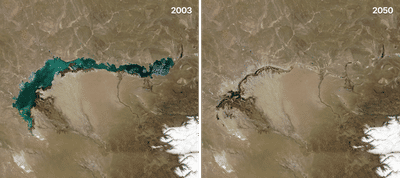

Similarly, Aigerim Kapar's Memories of Lake Balkhash 17 explores the ecological consequences of Soviet infrastructural expansion in Kazakhstan. Written from a speculative future, Kapar's essay envisions Almaty in 2050, where toxic dust storms and water scarcity have made daily life unbearable. By collapsing past, present, and future, she exposes how Soviet-era industrialization—deeply linked to military expansion—has disrupted critical infrastructures that once sustained nomadic communities. Drawing on the concept of critical infrastructure 18—which includes landscapes, traditions, and everyday practices—Kapar connects the disappearance of Lake Balkhash not only to climate change but also to colonial violence, which erased indigenous land relations and traditional knowledge systems.

Economic Reordering

Militarisation does not always remain invisible. Some areas are rapidly and radically transformed by war, such as the economy. Economies of the Aftermath 19 by Nazar Golianych explores how economies change during russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in Mariupol, "where the dynamics of survival, resistance, and exploitation continue to play out." 20 Analysing the complex processes of destruction of economic relations, grey economies, changing beneficiaries, and colonial practices. One of the key aspects of Golianych's study is the impact of occupation economies, where destroyed infrastructures are strategically repurposed by occupying forces to exert control. The systematic targeting of power grids, markets, and production facilities not only cripples economic activity but also creates dependencies that occupation regimes exploit. He documents how, in Mariupol, a sequence of deliberate infrastructure attacks led to a total collapse of basic services, forcing residents to rely on кussian-administered economic structures for survival. By incorporating Ann Laura Stoler's concept of "imperial debris," 21 Golianych frames post-war economies not as spaces of renewal but as sites of extraction and domination.

eeefff. The School of Algorithmic Solidarity. State of things before the session in ACUD, 2024, Berlin. Courtesy of eeeff (https://eeefff.org/en/projects/algorithmic-solidarity.html)

Digital Militarization

Digital infrastructures are also subjected to militarization. The eeefff collective, in their investigative research, Can Colonialism Be Encoded?, 22 examines the leaked source code of Yandex to reveal how algorithms embed violence, militarization, and imperialist imaginaries at the level of hardcoded software. By analyzing the leaked 44.71-gigabyte dataset, eeefff uncovers how digital platforms like Yandex Maps alter territorial boundaries to fit russian geopolitical narratives, how electronic assistants are programmed to suppress certain war-related queries, and how logistical algorithms enforce precarious labor conditions for workers under militarized digital economies. The fusion of digital and military infrastructures extends imperial governance into algorithmic spaces, where maps, logistics, and search results actively reshape public perception and operational realities. As eeefff argues, borders are not just drawn on maps; they are encoded into the fabric of everyday technologies. This perspective highlights how digital infrastructures, like physical ones, serve as battlegrounds for control, discipline, and territorial expansion. More fundamentally, through The School of Algorithmic Solidarity, a collective investigation into the leaked Yandex code, eeefff is gathering evidence of cyber warfare, how violence unfolds at the level of code, how information terror is shaped.

The Weaponization of Home and Intimacy

Oleksii Minko's article, The Temporal Occupation of Ukrainian Housing by russia, 23 offers an incisive analysis of how intimate infrastructures—homes, neighborhoods, and domestic spaces—become targets of war and occupation. Minko describes how russian forces, through direct destruction and bureaucratic control, manipulate the affective and material aspects of housing to extend the reach of occupation beyond military frontlines. russian authorities appropriate housing by forcibly repurposing abandoned homes for military personnel and settlers while simultaneously making access to property dependent on acquiring russian citizenship. Filtration camps, forced passportization, and controlled real estate markets ensure that housing, once an intimate and personal domain, becomes a mechanism of governance and coercion. Weaponised intimate space exposes the failure of the division of the world into private and public spheres and shows that, in a situation of fragility and vulnerability, the home is a political space - both a controlled site and a place of resistance. However, the home is also an extended space: it is both physically shaped and bureaucratically rooted, as well as a personal memory and history. Therefore, violence continues to be realised and affected even when you are already many hundreds of kilometres away from your material home; the home as a locus of memory keeps under attack, carrying on the terror of intimacy. Minko's personal account of dreaming about returning to his hometown of Berdyansk illustrates how occupation operates on cognitive and affective levels. The home, once a sanctuary, is rendered unstable-even in the imagination-through the ever-present fear of surveillance, coercion, and betrayal.

The ruins of infrastructure

AWC Journal also refers to the concept of the ruins of infrastructure. 24 It sheds light on the possibility/impossibility of destroying infrastructure and analyses how infrastructures reproduce their militaristic and repressive potential even after dismantling, closure, and catastrophe.

Belarusian artist and researcher Hanna Paniutsich's The Alienation Zone: Radioactive Entanglements of Past and Present 25 explores the aftermath of nuclear infrastructures, focusing on the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, where Soviet-era energy policies have left lasting environmental and social impacts. Paniutsich's family comes from Paliessie, a region now within the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. For her, the study of the ruin of infrastructure – Chornobyl after disaster – is not only a political inquiry but also a deeply personal engagement with the destruction of her ancestral lands.

The Exclusion Zone, militarized from its inception despite the rhetoric of the 'peaceful atom,' embodies both a dormant war machine and a site of geopolitical terror. Its infrastructure, designed under militaristic logic, enables radiation to be weaponized, while forced displacement has severed centuries-old human-environment relationships. When Russian forces occupied Chornobyl in 2022, they reactivated its latent potential as a weapon, risking a new global catastrophe and exposing the inherent dangers of nuclear infrastructures.

The ruins of the infrastructure of Soviet modernity are foundational for the artwork "Druzhba" 26 created by Lithuanian artists Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas. The artists critically examine the Druzhba pipeline and its function as a geopolitical instrument of dependency. Their work reveals how infrastructural projects were designed not only to transport resources but also to bind territories into extractive networks that ensured long-term political subjugation. This legacy of infrastructural colonization continues to shape contemporary politics, as evidenced by russia's strategic use of energy infrastructures in its war against Ukraine. "The pipeline is not just a conduit for oil; it is a conduit for control," 27 they argue, highlighting how infrastructures shape economic dependencies that persist even amid geopolitical upheavals.

Resistance

In gathering material for the AWC Journal, we adopted an expanded interpretation of infrastructure, considering not only its material aspects but also its political and economic effects, emotional impact, and how it becomes embedded in and contributes to militaristic or violent systems, shaping relationships, inclusion/exclusion, and inequalities. 28 It seems crucial to us that the AWC Journal not only exposes various strategies of militarisation and weaponized civil initiatives demonstrating the totality of infrastructure. Fundamentally, the authors of the journal attempt to outline the potentialities of resilience tactics. If we try to conceptualise these strategies, three broad lines of possible resistance can be described: making the hidden tangible, fragility and disruption, and building alternative infrastructures.

Earlier, we pointed out that the infrastructure fears its invisibility –– making the hidden infrastructure tangible or visible –– is one of the most important resistance tactics. Infrastructure must be brought into focus to reveal how historical decisions, conflicts, and inequalities shape our current environment. 29 Various artistic forensic investigations have revealed the violent and political potential of spheres, practices seemingly unrelated to militaristic tendencies, just use this strategy. As in the artistic practices of eeefff and Sonya Isupova, their juxtaposition of scientific, artistic, and investigative tools helps not only to uncover the workings of the machinery of war in "non-military" spheres but also to gather evidence of criminality for future reflection to prove information terror and environmental terror correspondingly.

Disruption 30 is also one of the essential methods of dealing with infrastructure dependencies. The Anonymous Guide Planned Outage for Russian Military 31 demonstrates how fragile seemingly invincible infrastructures can be. With minimal resources—aluminum helium balloons, readily available in parks and shopping centers—critical elements of military logistics can be disrupted. By entangling power lines, balloons cause short circuits, forcing power outages that hinder communication, surveillance, and operational efficiency. This low-tech intervention highlights an inherent paradox: the military-industrial complex, built on high-tech weaponry and digital warfare, remains deeply vulnerable to small-scale disruptions.

Artistic strategies like this reframe sabotage as a form of creative resistance, bringing abstract infrastructures closer to everyday life. Instead of viewing power grids or data centers as distant, impenetrable systems, these acts make visible their weak points, revealing the extent to which militarization relies on precarious, interdependent networks. Infrastructure, often perceived as an unassailable force of control, is a network of contingent operations that can be destabilized by civilian ingenuity. In this sense, art does not merely document war—it intervenes in it, offering new ways to disrupt and subvert systems of oppression.

Sense of Safety international art project. Installation view. © YermilovCentre | photo by Andrei Stseburaka

Infrastructure is not solely a tool of control and violence; it also serves as a catalyst for transformation. Building alternative futures necessitates the creation of new infrastructures—systems that support survival, continuity, and renewal. 32 Natasha Chychasova's Adaptive Violence: How War Transformed Institutions and Art 33 illustrates how the war in Ukraine has turned cultural spaces into both targets of destruction and sites of resilience. The systematic looting and erasure of museums, galleries, and archives by russian forces reflect a broader strategy of colonial domination—one that seeks not only to occupy land but to erase cultural memory. Yet, in response, artists and cultural institutions have adapted, transforming their practices into forms of direct action. Art spaces, such as YermilovCentre in Kharkiv, the Lviv Municipal Art Center, and the Dnipro Contemporary Cultural Center, have become bomb shelters, humanitarian hubs, and centers of communal care. Art initiatives underscore the necessity of parallel infrastructures—ones that function outside state-controlled mechanisms and provide continuity amid destruction.

As Chychasova notes, war does not end artistic practice; it forces its transformation. By reshaping cultural production into acts of care, resistance, and solidarity, artists carve out spaces where memory and agency persist despite systemic attempts at erasure. In this context, art becomes not only a means of survival but an active tool for reclaiming the present and envisioning a future beyond war.

Footnotes

- 1Metasitu. (2016). States Status Statues and Statutes [Artwork]. antiwarcoalition.art. Retrieved From ttps://Antiwarcoalition.Art/Works/6qua7wcbjvsh6bduix2u?P=

- 2VDNKh is a former Soviet Expo site inaugurated in 1939 as a tool to broadcast the achievements of the Soviet Union.

- 3Chychasova, N. (2024). Adaptive Violence: How War Transformed Institutions and Art. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 131–141

- 4Wolfe, P. (1999). Settler colonialism and the transformation of anthropology: The politics and poetics of an ethnographic event (Writing past imperialism). London and New York: Cassell, P.2

- 5Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, P. 329

- 6Tsing, A. L. (2019). Supply chains and the human condition. Urban Geography, 40(10), PP. 1457-1472

- 7Total Military Insight. (n.d.). Smart base infrastructure: The future of military operations. Retrieved from https://totalmilitaryinsight.com/smart-base-infrastructure/

- 8Konieva, M. (2024). Community, Science, and Art: Mutual Support in Times of War. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP.106-121

- 9Ibid

- 10Cowen, D. (2017). Infrastructures of empire and resistance. Verso. Retrieved from https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance

- 11Dika, A. (2024). Military on the coast in times of peace. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 122-130

- 12Matviyenko, S. (2023). Vertical occupation. London Ukrainian Review. Retrieved from https://www.londonukrainianreview.org/posts/vertical-occupation

- 13Goncharenko, L. (2024). The weaponization of ecosystems: Historical and contemporary parallels. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 68-75

- 14Ibid.

- 15Isupova, S. (2024). Revealing the landscape: Mapping cyclical history of colonial infrastructure of the Kakhovka Dam. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 54-62

- 16See articles by Malysheva, N., & Hurova, T. (2023). Legal aspects of the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam: Ecocide and accountability. Journal of Environmental Law & Policy, 4(1), PP. 84-104; Gillett, M. (2023). The Kakhovka Dam and ecocide: Legal and environmental implications. International Law Journal, 5(2). Retrieved from https://intr2dok.vifa-recht.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/mir_derivate_00015517/The_Kakhovka_Dam_and_Ecocide.pdf

- 17Kapar, A. (2024). Memories of Lake Balkhash. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 63-67

- 18Huson, F. (2022). Fighting invasive infrastructures: Indigenous relations against pipelines. Environmental Humanities, 14(2), 201-219.

- 19Golianych, N. (2024). Economies of the aftermath. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 42-53

- 20Ibid

- 21Stoler, A. L. (2013). Imperial debris: On ruins and ruination. Duke University Press.

- 22eeefff . (2024). Can Colonialism Be Encoded? AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 16-30

- 23Minko, O. (2024). The temporal occupation of Ukrainian housing by russia. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 31-41

- 24Borisionok, A., & Stebur, A. (2023). If disrupted, It becomes tangible. Infrastructures and solidarities beyond post-Soviet condition [Exhibition]. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius. Retrieved from https://www.if-disrupted.lt

- 25Paniutsich, H. (2024). The alienation zone: Radioactive entanglements of past and present. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 84-92

- 26'Druzhba' means 'friendship' in russian

- 27Kochubinska, T. (2024). System of Dependency: "Druzhba" project by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas Interview. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 93-105

- 28Spice, A. (2022). Fighting invasive infrastructures: Indigenous relations against pipelines. In J. Dhillon (Ed.), Indigenous resurgence: Decolonialization and movements for environmental justice (Chapter 3). Berghahn Books, P. 49

- 29Robbins, B. (2007). The smell of infrastructure: Notes toward an archive. Boundary 2, 34(1), P.32

- 30Borisionok, A., & Stebur, A. (2023). If disrupted, It becomes tangible. Infrastructures and solidarities beyond post-Soviet condition [Exhibition]. National Gallery of Art, Vilnius. Retrieved from https://www.if-disrupted.lt

- 31The Anonymous Guide. (2024). Planned Outage for Russian Military. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 76-83

- 32Cowen, D. (2017). Infrastructures of empire and resistance. Verso. Retrieved from https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance

- 33Chychasova, N. (2024). Adaptive Violence: How War Transformed Institutions and Art. AWC Journal, Entanglement of Infrastructures: Civilian Systems under the Pressures of Militarization Issue 1. PP. 131-141